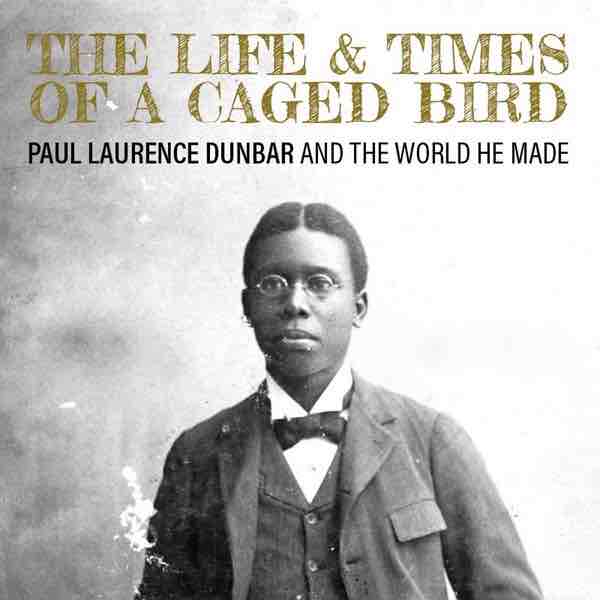

Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio on June 27, 1872. He died in Dayton, Ohio on February 9, 1906. In the years in between, according to Gene Andrew Jarrett’s new biography, Paul Laurence Dunbar — The Life and Times of a Caged Bird (Princeton University Press 2022), he became the most multifaceted professional African-American writer of the turn of the century, successful in the high culture of poetry, fiction, and essays and popular culture of vaudeville, lyrics and theater.

Jarrett’s subtitle describes Dunbar as a caged bird which is the subject of Dunbar’s most famous poem, Sympathy. Published in 1899, Sympathy’s poetic metaphor compares a caged bird to the legacy of slavery, racial segregation and social discrimination that was the blight of African Americans in post-Civil War America. Maya Angelou used the final line of the poem as the title of her 1969 coming-of-age novel I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

For Ohioans Dunbar is a literary treasure who is often overlooked until someone brings up his name during Black History Month and then we put him away until next February. In 1975 the United States Post Office issued a ten-cent stamp with his image. You can visit his home in Dayton thanks to funding from the state of Ohio. But to most modern-day Americans, of all races, he has been largely forgotten. Through his 2022 biography Jarrett, Dean of the Faculty at Princeton University, hopes to shed new perspectives on Dunbar and insights into his life and the times in which he lived.

For much of the 19th century and especially at the end of the Civil War, Ohio was a haven for former slaves. Joshua and Matilda Dunbar were two such individuals who left Kentucky to find a better life. They settled in Dayton, where their son Paul was born. Joshua, a Civil War veteran who struggled with alcoholism and had a history of domestic violence, deserted his family shortly after arriving in Dayton, leaving Matilda to raise Paul and her two sons from a previous marriage alone. Jarrett puts a great deal of emphasis — maybe too much — on this family history of alcoholism and violence on the younger Dunbar’s life.

Receiving his early education in Dayton’s segregated classrooms, Dunbar enrolled in the all-white public high school and became the only Black student in his graduating class. He served as president of the school’s literary club. In 1889, at age 16, two years before his high school graduation, Dunbar had his first poem published in a Dayton newspaper. Orville Wright, who would go on to be famous along with his brother Wilbur in the field of aviation, was his friend and high school classmate. In later years, Wright would assist Dunbar in advancing his career.

In the late 19th century, going to college and advancing his studies was not an option for Dunbar. But this did not deter him from making his literary voice heard. Taking a job in Dayton as an elevator operator at four dollars a week, he continued to write, literally between floors.

After obtaining some success as a writer, he was able to get a clerkship at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. This allowed him to take classes at Howard University, but his lack of a college degree prevented him from ever obtaining his goal of teaching at a college.

Since Dunbar did not keep a diary or a journal to record his inner thoughts, Jarrett relies heavily on letters between Dunbar and Alice Ruth Moore, a native of New Orleans who would become his wife, along with letters to his mother and correspondence with friends. Alice was a poet, teacher, and literary person in her own right, which added to their mutual attraction. After engaging in a two-year long correspondence before they met face to face, they married in 1897.

Their marriage had its ups and downs. He was prone to flirtations with other women, allegations of violence and alcoholism. They struggled financially and spent long periods apart, as she continued in her teaching career, and he attempted to make a name for himself. They stayed together until 1902 when they permanently separated — never to see each other again, but they never divorced.

In addition to publishing his poetry, short stories, novels and theatrical works, Dunbar was extremely popular in appearances before audiences where he read his poetry. It is hard for 21st century readers to think that a poet, especially a Black poet, would draw large audiences to hear a poetry reading — but such was life in the turn-of-the-century America, and these performances accounted for much of Dunbar’s income. But his declining health around the turn of the 20th century cut short many of his appearances.

Jarrett’s writing is not for the average reader. With his academic style, completing the 460 pages of text can be challenging. But for the serious reader, the book is worth the effort.

To add to the complexity for modern day readers, many of Dunbar’s works — which are widely reprinted in the book — are written in the Negro dialect associated with the antebellum South. This genre is not popular in today’s world and is sometimes difficult for contemporary readers to comprehend.

Through his poetry and writings, Dunbar was associated with such luminaries as Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, James Weldon Johnson and Booker T. Washington. He corresponded with Theodore Roosevelt. The novelist William Dean Howell was one of his mentors. He traveled in elite circles and was a very prominent figure in African-American life. But he was always a Black writer struggling to survive in a world where white authors dominated, and he had to cope with his personal demons.

Dunbar’s death from tuberculosis at age 34 cut short his literary career. But his works should not be forgotten. He made a significant contribution to African-American literature — including nine books including novels and short story collections, more than 425 poems, numerous essays, and theatrical productions, upon which future generations of writers could build. Jarrett’s biography will hopefully spur a revival of Dunbar’s works and a recognition by Ohioans of the literary gem who once lived among us.

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she serves on the Board of the Ohio History Connection, is currently vice president of the Cuyahoga County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission and past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.

One Response to “BOOK REVIEW: A New Look at Paul Laurence Dunbar by C. Ellen Connally”

Peter Lawson Jones

Thank you, Your Honor, for this review. A wonderful synopsis of what is, apparently, a challenging, but worthwhile, read.