When historians rank presidents of the United States, Warren G. Harding — the last president from Ohio — almost always comes in somewhere near the bottom of the list. In a recent poll by the Siena Research Institute, Harding came in third from the bottom, ahead of Donald Trump and James Buchanan.

Harding was the elected in 1920, defeating fellow Ohioan, Democrat James Cox. His administration was rife with scandals including the infamous Teapot Dome Scandal, which surfaced after his death, along with allegations that he had fathered a child out of wedlock.

While Harding may have had his shortfalls, one thing is clear: he understood Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution which grants the president the power to grant pardons. It reads as follows “…and he (the President) shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States except in cases of impeachment.” It’s kind of a “get out of jail free card” that the president can deal at his discretion with no checks and balances from the legislative or judicial branch. For clarification, pardons do not apply to state charges. Theoretically, a person who receives a presidential pardon could be subject to prosecution by a state court for the same acts if they violated a state law.

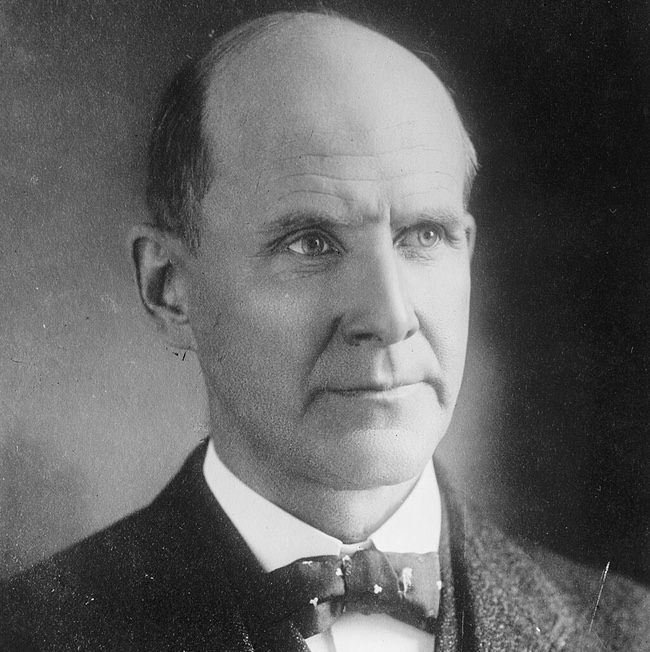

Harding granted 800 pardons during his tenure from March 4, 1920, to August 23, 1923. That number is somewhere in the middle range of pardons compared to other presidents before and since. However, the 1921 commutation of the sentence of prominent Socialist trade unionist, political activist and perennial presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926) stands out as his most notable.

On June 16, 1918, Debs gave a speech in Nimisilla Park in Canton, Ohio, to address the more than a thousand of the faithful who had gathered for the annual picnic of the American Socialist Party. A long-time pacifist, in his speech Debs denounced America’s involvement in World War One and urged resistance to the draft.

In addition to the local Socialists in attendance, the crowd also included federal agents, newspaper reporters and a stenographer who recorded speeches for prosecutors considering criminal charges against Debs. Local vigilantes also worked the crowd looking for slakers, an early 20th century term for draft dodgers. Whenever they spotted a young man, they insisted on seeing his draft card.

Debs was arrested on June 30, 1918, and charged with ten counts of sedition—which is the legal term for engaging in conduct that incites a rebellion or violence or aims to undermine or overthrow the government. The extent of his alleged criminal activity was giving a speech. But Debs had incurred the wrath of the Wilson Administration to such an extent that President Woodrow Wilson called him a traitor to our country. Sounds like Letitia James, James Comey and John Bolton

Debs was tried in federal court here in Cleveland. The trial drew national headlines and was of such note that when a history of the U.S. Federal Court for the Northern District of Ohio was published in 2012, an entire chapter is devoted to the proceedings.

On September 14, 1918, Debs was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison. He appealed his conviction, but the Supreme Court said that his conduct, by making a speech, had the intention and effect of obstruction of the draft and military recruitment.

On April 13, 1919, Debs started his ten-year sentence in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. Unionists, Socialists, anarchists and Communists in Cleveland held a massive parade on May 1 of that year to voice their opposition. It was one of the largest demonstrations ever held in the city. When marchers marched down Superior Avenue toward Public Square, they were confronted by mounted police, army trucks and tanks. Casualties amounted to two people killed, forty injured and 116 arrested.

In 1920, Debs made his fifth and final run for president. He had been the first Socialist candidate for president in 1900, and he ran again under the Socialists banner in 1904, 1908 and 1912. His 1920 campaign featured campaign buttons that said, “For President: Convict No. 9653.” While an inmate at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary Debs received 914,191 votes or 3.4% of the voted.

In March 1921, shortly after Harding was inaugurated, Debs met with Harding’s Attorney General, Ohioan Harry Daugherty. Debs was 66 years old, in poor health and at the risk of dying in prison. Harding, recognizing Debs’s popularity and questioning the rationale behind his conviction, was concerned that Debs would die in jail and become a martyr.

In a series of events that are hard for the 21st century public to believe, Debs was given a pass from the federal penitentiary in March of 1921. He boarded a train and went to Washington where he met with the Attorney General. After what was described as lively discussion about government, religion and socialism, Debs got back on the train and went back to prison. All the while, traveling alone.

On December 23, 1921, Harding commuted Debs’s sentence to time served. Fellow inmates sent him off with a “roar of cheers” and a crowd of 50,000 greeted his return to his hometown of Terre Haute, Indiana, to the accompaniment of a brass band. The day after Christmas, Harding welcomed Debs to the White House, telling him, “Well, I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet your personally.”

Debs spent the remainder of his years trying to recover his health, which was severely undermined by prison confinement. He died in 1926.

Compare Harding’s decision to that of the current resident of the White House. On October 17, Trump commuted the sentence of disgraced Congressman George Santos who pleaded guilty to internet fraud and aggravated identity theft. He scammed the public, misused campaign funds, repeatedly lied and even cheated a disabled veteran who sought funds to defray the cost of medical treatment for his dog. Trump also forgave all fines and orders of restitution imposed on Santos. Trump’s rational? Santos always voted Republican.

So who was the better president —Harding or Trump? Historians and the American people will have to decide.

If you are interested in the topic of presidential pardons, I recommend The Pardon — The Politics of Presidential Mercy by Jeffrey Toobin (Simon & Schuster, 2025). Toobin explains pardons within the context of the Nixon resignation and subsequent pardon by President Gerald Ford. He also gives the reader much to think about. It is time that we the people amend the Constitution to prevent this president or any other president from exercising unchecked power when it relates to pardons and commutations.

Get out of jail free cards should only be played in Monopoly. They should not be used to thwart the judicial system or to allow the president to reward friends and supporters.

Who will Trump pardon next? The January 6 insurrectionist who has already received one pardon for storming the capital is now in legal trouble again. This time he threatened the life of Democrat Hakeem Jeffries. Since Jeffries is clearly not a presidential favorite, no one will be surprised if Jeffries’ assailant gets a pardon.

Only in America and dictatorships around the world!

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she is a former member of the Board of the Ohio History Connection, and past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table, and is currently vice president of the Cuyahoga County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.