In 1975 the Cleveland Indians made baseball history when they hired Frank Robinson as the first Black manager for a Major League Baseball team. Robinson’s ascendency to a position of leadership came 28 years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line when he went to bat for the National League Brooklyn Dodgers in April of 1947.

While Jackie Robinson and Dodgers Manager Branch Rickey have become the face of the integration of MLB, the role of the Cleveland Indians has often been overlooked. In July of 1947 Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck signed a contract with Larry Doby breaking the color line in the American League. The following year Veeck signed Satchel Paige. Doby and Paige would go on the be the first African American players to win a World Series when the Indians won the crown in 1948.

But on the eve of the signing of Jackie Robinson, Indians legend Bob Feller was clear in his opposition to the integration of the national pastime. “There isn’t a Black player in America talented enough to compete with white players currently in the game,” he said.

While Feller was outspoken in his opinion, his was the consensus of most players and owners. For decades owners of MLB teams, had an unwritten law — Black players need not apply. Blacks could play in the Negro leagues, but MLB was a white man’s game.

Howard Bryant, a noted sports analyst who has written eleven books dealing with various aspects of sports history, chronicles the racism endemic in the psyche of the owners and players of baseball for most the first half of the 20thcentury in his new book, Kings and Pawns — Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America (Mariner Books: 2026).

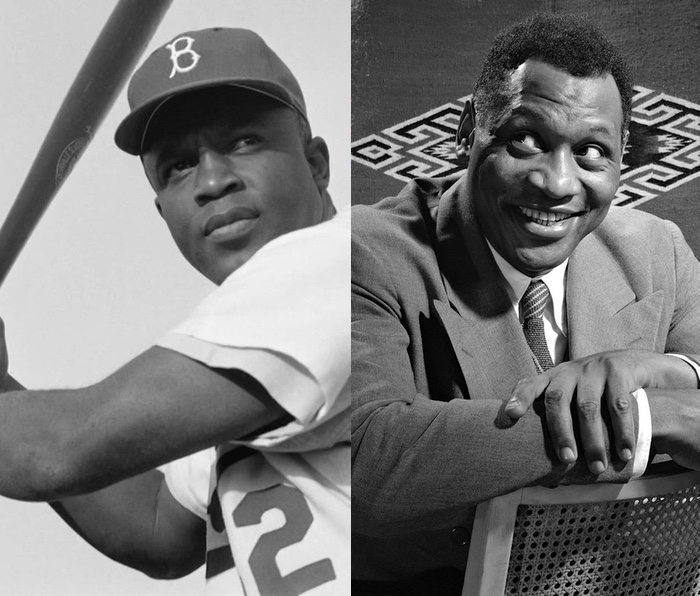

The book focuses on the July 18, 1949, testimony of Jackie Robinson before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The subject of testimony was Paul Robeson.

Robeson, who was an iconic sports and entertainment figure during the early part of the 20th century, had broken the color line by playing football at Rutgers — one of only three Black students at the university — and becoming an All American in 1917. After graduating from Rutgers as valedictorian and graduating from Columbia Law School, Robeson turned to singing and acting, becoming the first Black man to play the role of Othello, first in London and then on Broadway — which at the time was a monumental event, since the Shakespeare classic involves a relationship between a Black man (a Moor) and a white woman.

In April 1949, Robeson gave a speech before the Soviet-sponsored World Peace Congress in Paris, which raised long-held questions about his patriotism. Robeson had visited the Soviet Union multiple times during the 1930s and felt that he was treated better there than in the United States. At least there were no signs of open segregation, as there were in the American South. In his speech, he questioned whether American Blacks would or should fight on behalf of the American government against the Soviets, if a war should occur, citing the oppression of Blacks in America for generations by means of lynching, disenfranchisement and segregation.

His comments drew the ire of the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover and members of the House Un-American Activities Committee, a committee who was notorious for asking American citizens if they “are now or were a member of the Communist Party.” In the era of the “Red Scare,” any connection to the Communist Party, no matter how remote, was the kiss of death for anyone in public life.

Robinson, who by 1949 was the nation’s premier Black athlete was asked to appear before the committee to denounce Robeson as a traitor. He was not under subpoena and was not compelled to appear. But following the advice of his mentor, Branch Rickey, Robinson chose to appear. He tried to walk a narrow line and not denounce Robeson but ended up saying “If Mr. Robeson actually said that Black Americans would not fight in a war against the Soviets, such a statement seemed rather ‘silly’.”

The ultimate question for the reader and for historians is whether Jackie Robinson was a pawn in the hands of white politicians and Branch Rickey? Did he sell out another Black man? Rickey, whom Hollywood and the media have painted as the great white liberal who was fighting for integration, comes across as anything but as portrayed by Bryant.

After Robinson’s testimony, Robeson was blackballed. He was written out of sports history. His name was removed by the list of NAACP awardees. He could not get work. Rutgers deleted his name from their Football Hall of Fame. The United States government refused to issue him a passport which destroyed his singing career which was centered in Europe. It took a Supreme Court decision ten years later for Robeson to get his passport back. Robeson died in 1976, living the final years of his life in obscurity, virtually written out of most history books.

Robinson would retire from baseball at age 37 in 1957. He was not given a job in MLB. He was always associated with the Republican party, campaigning for Richard Nixon in 1960. Many have labeled him as a conservative integrationist. Others use terms that are not so kind. Unlike Robeson, who was more akin to a Muhammed Ali or a Colin Kaepernick who were outspoken advocates for racial equality, Robinson was anything but an activist. He made no comment when Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi in 1955 or about Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a bus in Montogomery, Alabama. He passed on going to the 1963 March on Washington.

Bryant goes in depth to discuss the lives and historical impact of two complex individuals. Both men were kings, but were they also pawns in a society that pitted one Black man against another?

At times, Kings and Pawns is not an easy read. Readers without a background in American history during the middle years of the 20th century may struggle. But it is worth the struggle. The book gives a clear picture of the politics and racism of baseball in the 20th century and today. For baseball fans Kings and Pawns is a must read.

In 1997, MLB retired Robinson’s Number 42, making it the first number to ever have that status. While several players still had the number that year, no new player could use that number again. In death, thanks to the work of his now 103-year-old wife Racheal, Jackie Robinson remains an iconic and legendary figure, much more than he was at the time of his retirement.

After reading this book, I stopped at my favorite haunt, the Beachwood Branch of the Cuyahoga County Library. I asked the librarian if they had a biography of Paul Robeson. His response was “Who?” I had to spell out the name.

I was not surprised to find that there was no work on Robeson on the shelf at the branch library, so I asked to have one ordered. To my shock, I found that the County Library system does not own a single biography of Paul Robeson. I’m sure that Cleveland Public Library has multiple titles. Amazon has at least ten. The librarian assured me that he would order Kings and Pawns.

By way of a footnote, Bryant points out that there were more Black players in the league when Robinson died in 1972 than there are playing in the majors today. Black players dominate the NBA and the NFL, but Hispanics and whites dominate MLB. Maybe history is repeating itself.

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she is a former member of the Board of the Ohio History Connection, and past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table, and is currently vice president of the Cuyahoga County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.