By C. Ellen Connally

In the wake of the Trayvon Martin verdict, there continues to be a great deal of debate and activism over the merits or demerits of the so-called “stand your ground” law. While this law is pivotal in cases of self defense and was the focal point of much of the public discourse after the death of the seventeen-year-old Florida youth, there is another aspect of the trial that has been largely overlooked.

That issue is the decision by the Florida legislature to allow juries of six persons to reach a verdict in felony cases rather than the traditional twelve-person jury. The questions is, would a twelve-person jury in the George Zimmerman case have rendered a different verdict?

The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution insures the right to a trial by jury in criminal cases — a concept that goes back to the Magna Carta. However, the Constitution does not delineate the prescribed number of jurors, a decision that is made by the individual states. Students of legal history are not sure why the tradition of twelve jurors developed — a tradition that goes back to the English Common Law. Legal historians speculate that the tradition of a twelve-person jury could have evolved from comparisons to the twelve apostles, possibly the twelve tribes of Israel, the twelve signs of the Zodiac, the twelve months of the year or the centrality of the number twelve — no one knows for sure.

Starting in the 1970s and coming to fruition in the 1980s, judicial reformers decided that courts could operate more efficiently with less than twelve jurors. The purported advantages of reducing the size of jury panels include saving time, money and resources by simply calling fewer citizens. Since most people don’t want to serve on jury duty anyway, the movement gained popular support. In addition, with fewer jurors, judges and prosecutors saw it as a way to reduce the length of time for jury selection, trials and deliberations. The long and short of it was that it was all about saving time and money — which became commonly known by the buzz words “judicial efficiency.” But critics of these reductions raise legitimate objections.

The primary question is whether the reduction in the number of jurors alters the ability of the jury to render a just verdict. Critics correctly point out that the smaller the jury, the less likely the jury will be representative of a cross section of the society — which is exemplified by the six woman jury in the Zimmerman case.

If the selection process had required twelve tried and true citizens, the chances of having a jury panel with a variety of racial, social, educational, occupational and economic backgrounds would be high. There would also be greater odds of having persons with varying levels of intestinal fortitude to stand their ground on their interpretation of the evidence, persuasiveness of the oral arguments and application of the jury instructions.

While the Supreme Court has ruled that a black defendant does not have a constitutional right to have at least one black person on the jury, the perception of justice is better served when a jury is made up of divergent races, sexes, social classes and background. Prosecutors and defense counsel who know that they have a weak case will often tailor their arguments to the one member on the jury that they feel will be the most sympathetic to their case, hoping for a hung jury. One side or the other may not be able to win over twelve jurors but if they can convince just one — raise reasonable doubt in the mind of just one person — the case can result in a hung jury and a second bite at the apple.

Aside from the varied background of the jurors, consider group dynamics. In a group of six, the talkative “loud mouth” wins out far more easily than in a group of twelve. In a group of twelve, factions easily form and the lone holdout does not have to stand alone.

Movie buffs will recall the 1957 classic TWELVE ANGRY MEN. The story surrounds the deliberations over the fate of an 18-year-old New Yorker who is charged with killing his father. Juror #8, played by Henry Fonda, is initially the sole vote for acquittal. Juror #7 has baseball tickets and wants to vote for guilty and get to the game. Juror #10 believes that all people living in the slums are likely to commit murder.

But Fonda suggests that they take a secret vote without his participation. If the vote turns out eleven for guilty, Fonda agrees to go along with the majority. But the secret vote reveals that Fonda has an ally — there is another vote for not guilty. From there the house of cards for a guilty verdict begins to fall as individual jurors reveal many aspects of their life experiences that they bring into the jury room. Factions begin to form — open discussions occur and minds are changed. Reasonable doubt is debated and finally jurors are not so convinced that the defendant is guilty. The point is that the dynamics of twelve people making a decision is substantially different than six.

Consider the last time you were with a group of twelve people and the question was where to eat lunch. With six hungry people, hungry diners will cave in and agree to go with the crowd — even though they really wanted Chinese over Mexican. With twelve participants in the decision making process, splinter groups form and it is less likely that all twelve will end up lunching together. Such group dynamics are well documented by experts in jury deliberations and are key to understanding the decision in the Zimmerman case.

If Juror B 29 had been joined by at least one other juror who maintained that Zimmerman was guilty of something , maybe she could now sleep nights and not “carry Trayvon on her back.” Would additional jurors have resulted in a hung jury, a different verdict or a compromise verdict? Could Juror B 29 have been the Henry Fonda of the Zimmerman jury? With six jurors unlikely — with twelve possible.

Hindsight is always 20/20 and pundits will debate what the prosecution and the defense should or should not have done in the Zimmerman case until the next big trial comes along. Demonstrators should continue to demand “Justice for Trayvon” with demands to repeal the “stand your ground” law and restrictions on the ability of “want-to-be cops” to voluntarily take it upon themselves to troll our neighborhoods for suspects who just happen to look different than the majority of residents. But everyone from activist to bar associations should step back and consider that less is not always better in our system of jury trials.

The reduction of juries from twelve persons to six has created a jury system in Florida that allows for juries that are less than representative of the community at large. Countless defendants — black, white, male, female, gay or straight — who did not have a fair cross section of society to stand in judgment of their case were weighed on an unbalanced scales of justice tipped in favor of so-called judicial efficiency over basic fairness. The tradition of twelve jurors has lasted for centuries. The jury system of twelve persons was not broke — so why did the Florida legislature try to fix it.

When any large and identifiable segment of the community is excluded from jury service, the effect is to remove from the jury room qualities of human nature and varieties of human experience, the range of which is unknown and perhaps unknowable. It is not necessary to assume that the excluded group will consistently vote as a class in order to conclude, as we do, that its exclusion deprives the jury of a perspective on human events that may have unsuspected importance in any case that may be presented.

–Justice Thurgood Marshall, Peters v.Kiff (1972)

United States Supreme Court

[Image: Debra Sweet (Flickr)]

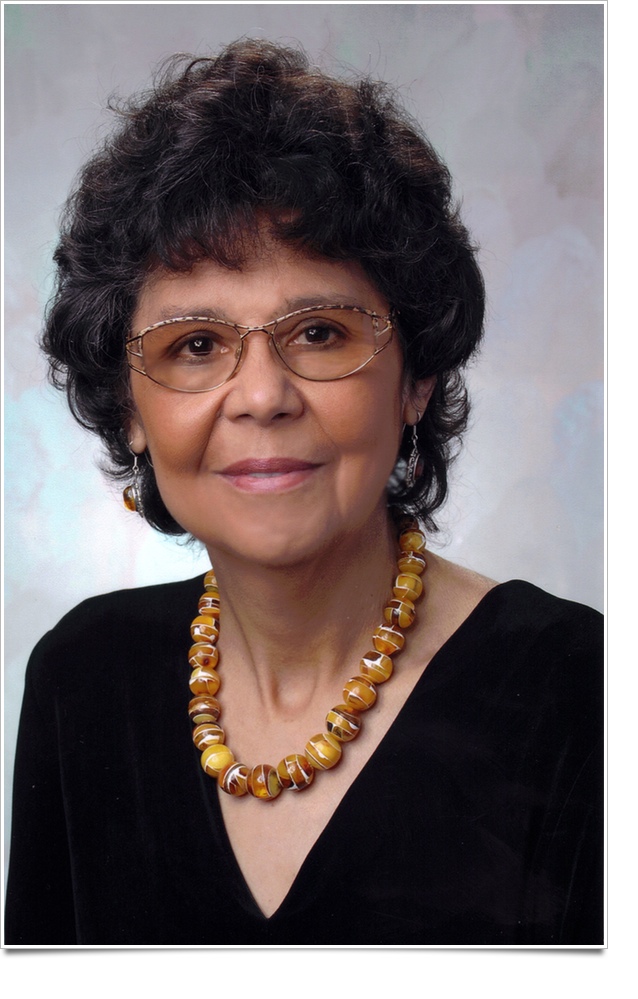

C. Ellen Connally is President of the Cuyahoga County Council (Democrat – District 9) and a former Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. She holds a BS from Bowling Green State University; a JD from Cleveland State University; a Master in American History from Cleveland State University and is a PhD Candidate in American History from the University of Akron.

C. Ellen Connally is President of the Cuyahoga County Council (Democrat – District 9) and a former Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. She holds a BS from Bowling Green State University; a JD from Cleveland State University; a Master in American History from Cleveland State University and is a PhD Candidate in American History from the University of Akron.

3 Responses to “REFLECTION: Six Versus Twelve and The Fate of Trayvon Martin”

SpaceArt

Trayvn? A sad bizarre sorry affair where both were wrong, ANYTHING could have happened and took on life of own…People could have been smarter about it, just ‘observed’, not push issues but instead turned into this free for all…Zimmerman IS paying but not ultimate loss Trayvn paid..I CAN understand WHY trayvn reacted way did…I would have reacted same way tooo but then again I am a white midaged guy and maybe NOT have gotten the same 10 th degree interrogation….THIS is just one of those endless debates and sore points ….

SpaceArt

PS…I aint that @mail or website but indicator of what to expect in the future…Goood luck with that…take a look at our econ…land of Freakonomics and Zombie Nation meets GeekWeek and whatever econ survivors still out there… Saviors are DMPs,nonprofts,soup kitchens and dollar stores…

SpaceArt

I read and agree with what the judge says….IF any solace ZIMMERMAN could get hit with civil suit,POOR employment prospects UNLESS wants to get tied to some ‘group’ TRYING to make some ‘points’which could have OWN bad bizarre affects AND HE gets dragged into OTHER legal action… I am surmising that. Life and legalities took on own disdynamics…