May 17, 1979 marked the 25th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education. In recognition of the date, President Jimmy Carter hosted a White House reception honoring notable African Americans who had been involved in the struggle to end segregation. President Carter also took the occasion to announce the appointment of Nathaniel R. Jones to a judgeship on the Sixth Circuit Federal Court of Appeals — a judicial district that includes Ohio.

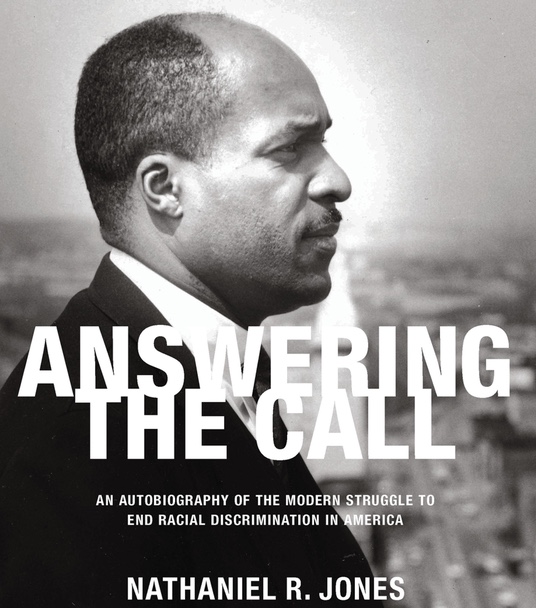

In his newly released autobiography entitled Answer the Call — An Autobiography of the Modern Struggle to End Racial Discrimination in America – the now retired judge admits that as the President spoke those words he “momentarily felt like he was in a dream.”

For the last ten years, Nathaniel R. Jones had served as general counsel for the NAACP, the organization that had fought so long and hard for the decision in the Brown Case. And now a soldier in the fight, someone who had argued for the implementation of the Brown decision before courts around the country, including the United States Supreme Court, would go from being an advocate to a decision maker and sit on the second highest court in the land. President Carter was making a strong statement.

In an extremely readable work that chronicles his life and philosophy, Jones tells the story of his humble beginnings in Youngstown, Ohio; his struggles in the civil rights movement; his eventual elevation to the bench; and now his life in the age of Barack Obama.

There are two significant themes in the book. One is the influence of Youngstown Attorney J. Maynard Dickerson on the young Nathaniel. Starting with their first encounter, when Jones was in his early teens, Dickerson served as a mentor and father figure who had a profound influence on Jones’ life and career — a fact that he continues to recognize and show appreciation for throughout the book.

The other is the challenge set forth by the founders of the NAACP. As it came to be known, The Call implored Americans of all races to discuss and protest racial problems and to renew the struggle for civil and political rights. This motto, along with the role of Dickerson in his life, would shape every aspect of Jones’ life and career.

Like many children of the Great Migration, Jones tells of his coming of age during the Great Depression and the struggles of his family to survive in the new world of the North. Although his family resided in a racially mixed neighborhood and Jones attended integrated schools, he describes life in Youngstown as a “form of societal schizophrenia in which the two races engaged and disengaged.” The color lines were clearly drawn and each side knew where they could and could not go.

After serving in a segregated Army during World War II, Jones returned to Youngstown and was able to use his GI Bill to complete college and night law school. His relationship with Dickerson opened many doors and his work in several Democratic campaigns provided him with what contemporary job seekers call “networking,” providing him with contacts that were beneficial to his future.

Laying the background for his future work as a civil rights lawyer, early in his career Jones served as the executive director of the Youngstown Fair Employment Practices Commission. In 1962 he became the first African American to be appointed an assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Ohio. In 1967 President Lyndon Johnson appointed him assistant general counsel for the Kerner Commission, which dealt with issues of race in America.

In 1969, Jones was asked by NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins to serve as general counsel for the NAACP, where he would follow in the footsteps of Thurgood Marshall. For the next ten years he directed the litigation and legal battles of the NAACP. In this position he was an integral part of school desegregation cases around the country that sought to implement and fulfill the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education.

One of his first requests, after taking the position with the NAACP, was from the Cleveland branch of the NAACP, asking for legal assistance in their court battle with the Cleveland School Board. Clevelanders will find this section particularly interesting as Jones discusses the machinations of School Superintendent Paul Briggs and the late Arnold Pinkney, who was at that time president of the Cleveland School Board. Jones raises serious questions about the true intent of Pinkney during this court battle and whether or not he was in support of the actions of the NAACP to desegregate the Cleveland school — a story that should someday be told at length.

Jones devotes an entire chapter to Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court Clarence Thomas. Making his opinion of Thomas very clear, he titles the chapter “Justice Clarence Thomas and the Supreme Court Double Cross.” While first discussing Thomas’ limited experience before his appointment to the court, Jones demonstrates how Thomas took full advantage of affirmative action and now seeks to reverse it for those coming after him. In a point-by-point analysis, Jones describes Thomas as an intellectually dishonest individual whose reactionary states’ rights positions strike at the very heart of the civil rights movement. Those who viewed the recent HBO special on Thomas will particularly enjoy this chapter.

While much of the book concentrates on Jones’ work in the law and his legal career, he also reveals a personal side of his life as he tells the story of the tragic death of his first wife; his struggles raising his infant daughter alone; and how his work took its toll on his family life.

In 2002 Judge Jones opted to retire from the federal bench. During his 24 years as a judge, he made a significant contribution to American jurisprudence. But as a judge he was restrained from speaking out on the issues that had been so vital to him early in his career. In his new role as a private citizen, he is free to voice his opinions and he uses his autobiography to do so, in an often no-holds-barred fashion.

Lawyers and non-lawyers alike will be enthralled by the story of a man who grew from such humble beginnings to the pinnacle of success in a legal career that has spanned more than 60 years. Because of Judge Jones’ association with Cleveland and its legal community, Clevelanders will recognize many names and events that shaped the city’s history.

Nathaniel R. Jones is an unsung hero of the civil rights movement. His story should serve as an inspiration to young and old alike who face discrimination because of their race, religion, sexual orientation or gender. As the title states, the work is devoted to the life of an individual but it is also the story of a civil rights struggle and its impact on one man.

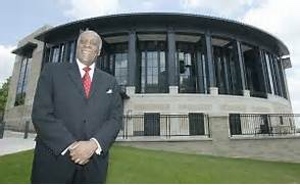

Today the Nathaniel R. Jones Federal Building and U.S. Court House stands in downtown Youngstown. The building, built on a former brownfield and only blocks from where the judge grew up, stands as a tribute to his contributions to our legal system and is a fitting monument to a man that truly answered The Call and made America a better place for all Americans. His autobiography will allow readers to have a deeper insight of not only the man but his movement.

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she serves on the Board of the Ohio History Connection and was recently appointed to the Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.

One Response to “BOOK REVIEW: Judge Nathaniel R. Jones: ‘Answering the Call’ by C. Ellen Connally”

Helen K. Wright

Your review will ensure my reading this book. You have touched another life.