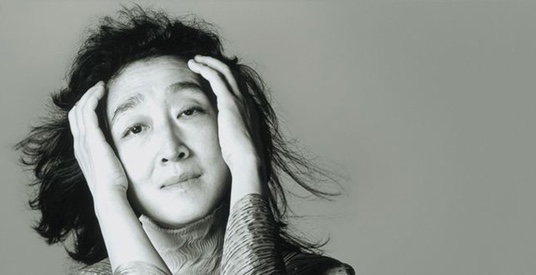

The final notes of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 32 still hung in the air of the hushed Mandel Concert Hall at Severance Music Center as pianist Mitsuko Uchida held her pose and slowly raised her hands from the Steinway piano’s keys. As she relaxed her body the packed house rose as one, yelling praise and clapping madly. Three curtain calls later, Uchida left the stage with the audience still applauding. They had just witnessed a master pianist present an impressive and long-to-be-remembered concert.

One of the most revered artists of our time, Dame Mitsuko Uchida is known as a peerless interpreter of the works of Mozart, Schubert, Schumann and Beethoven. Musical America’s 2022 Artist of the Year, and a Carnegie Hall Perspectives artist across the 2022/3, 2023/4 and 2024/5 seasons, and won the 2022 Gramophone Piano Award.

Born in Japan, Uchida moved to Vienna, Austria when she was 12 years old, after her father was named Japanese ambassador to Austria. She was enrolled at the Vienna Academy of Music and gave her first Viennese recital at the age of 14. She went on to a much-acclaimed career, much of it with the world-renowned Cleveland Orchestra. Her 2009 recording of the Mozart piano concertos nos. 23 and 24, in which she conducted the Cleveland Orchestra as well as playing the solo part, won the Grammy Award in 2011.

From 2002 to 2007 she was artist-in-residence for the Cleveland Orchestra. “Her 2015 performance with the Cleveland Orchestra elicited this review from the Plain Dealer: “Call it the mark of a master. Just when Mitsuko Uchida was starting to seem predictable, the goddess of purity, the pianist goes and exhibits another persona altogether. Performing Mozart again with the Cleveland Orchestra Thursday, the pianist-conductor treated listeners to a heartier, more robust version of her art.”

Each of Beethoven’s Sonatas 30, 31 and 32 have been described as “a haiku, beautifully formed, not wasting a note, making a very significant point.”

“In 1820 Beethoven had started work on not only the Ninth Symphony and the Diabelli Variations, but the Missa Solemnis as well. During this period of creative magnificence, he also produced his three final piano sonatas, each an experiment in form.”

Sonata 30 has been described as opening in a sweeping exhalation, like a speaker encountered in mid-sentence. Sounding like an improvisation, it ends as it begins, on the wing (when has a vivace sounded so calm?), and is followed immediately by an angry, prickly, minor-key prestissimo — briefer even than its predecessor. The final movement is a kind of balm. Technically a theme with six variations, the movement opens and ends in the warmth of serenity, daring not to conclude with a bang, but with a sigh.

It was obvious to anyone who knows Beethoven’s piano music that Sonata 30 was quite different than his earlier pieces. Sounding much more like “modern” music, part of this change was due to the transition of the piano and piano technique.

“In the period from about 1790 to 1860, the piano underwent tremendous changes that led to the modern structure of the instrument. This revolution was in response to a preference by composers and pianists for a more powerful, sustained sound. This was made possible by the ongoing Industrial Revolution, with resources such as high-quality piano wire for strings, and precision casting for the production of massive iron frames that could withstand the tremendous tension of the strings.”

“Piano technique evolved during the transition from harpsichord/clavichord to fortepiano playing, and continued through the development of the modern piano. Changes in musical styles and audience preferences over the Classical and Romantic periods, as well as the emergence of virtuoso pianists, contributed to the evolution of the piano and the various ‘schools’ of piano playing.”

Sonata 31 was met with critical raves when it was first presented. The reaction can best be understood by a modern program note which stated, “In none of the other 31 piano sonatas does Beethoven cover as much emotional territory: it goes from the absolute depths of despair to utter euphoria … it is unbelievably compact given its emotional richness, and its philosophical opening idea acts as the work’s thesis statement, permeating the work, and reaching its apotheosis in its final moments.”

Mitsuko Uchida presented all that emotional richness.

The obvious favorite segment of the program was Sonata 32 which had elements that sounded like the jazzy and melodic compositions of Scott Joplin and George Gershwin.

The last of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, the work was written between 1821 and 1822. It is one of the most famous compositions of the composer’s “late period” and is widely performed and recorded.

The work is in two movements, which breaks the traditional pattern of the three-movement sonata. Each is highly contrasting. The first movement is stormy and impassioned, “majestic” and brisk.” “The second movement is filled with drama and transcendence … the triumph of order over chaos, of optimism over anguish.”

Capsule judgment: Mitsuko Uchida’s recent Severance Hall all Beethoven concert proved once again that she is one of today’s premiere classic pianist.

Upcoming events of the Cleveland Orchestra:

Tickets: https://www.clevelandorchestra.com/

MOZART REQUIEM, MARCH 9-12

Legends swirl around the creation of Mozart’s Requiem, written on his deathbed and left unfinished: Who was the mysterious figure who commissioned the composer? What parts of the work were truly his own? And was Mozart composing his own funeral mass with this final artistic statement? Many of these questions were explored hauntingly (albeit suspiciously) in the movie Amadeus. We are nevertheless left with a work of overwhelming power — at once intensely dramatic and deeply personal — that touches the core of our humanity.

WEST SIDE STORY IN CONCERT, MARCH 17-19

Leonard Bernstein, complete film with Cleveland Orchestra, Brett Mitchell, conductor

THE TEMPEST STYMPHONY, MARCH 30 & APRIL 1

Shakespeare’s plays have provided a limitless source of inspiration, and this evening pairs two particularly evocative responses to his comedy The Tempest. First Thomas Adès, in his Cleveland Orchestra conducting debut, leads the world premiere of his Tempest Symphony, based upon the music from his 2012 opera. This is followed by Jean Sibelius’s Prelude and Suite that was assembled from incidental music he wrote for a Danish production of the play. Through this pairing, Adès explores the boundless nature of creativity and vast range of ingenuity.