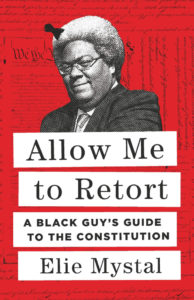

Author Elie Mystal is a columnist for The Nation and a frequent commentator on MSNBC. In his recently published book, he sets forth his interpretation of the United States Constitution. Peppered with salty language and cogent constitutional arguments, Allow Me to Retort – A Black Guy’s Guide to the Constitution (The New Press – 2022), analyzes various provisions of the Constitution from the perspective of Black Americans.

A graduate of both Harvard College and Harvard College of Law, Mystal wastes no time setting forth his premise. In the first sentence of the introduction, he shouts it out. “Our Constitution is not good” and “was designed to create a society of enduring white male dominance.”

Like the adage that asserts that a camel is a horse made by a committee, Mystal explains how sections of the Constitution came into being because of compromises resulting in a constitution made by a committee. In language that the seasoned historian and lawyer as well as the novice reader can readily understand, he explains how the framers of the Constitution made concessions to the South so that they could maintain their system of human bondage and at the same time sign onto a document that sets forth lofty assertions of freedoms and liberty, which applied mostly to white men.

The most glaring example is the Three-Fifths Compromise that provided for the counting of slaves as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of counting the population of the individual states. Southerners did not see slaves as persons and obviously not as citizens. But when it came to counting the population so that they could get more seats in the House of Representatives, Southerners wanted slaves counted. Northerners objected. If all those non-voting slaves were counted, the South would get too many seats and influence in the House of Representatives. As a compromise, they settled on counting three-fifths of the slave population. Northerners figured they were cutting their losses, but the so-called compromise still gave the South additional seats and power — not to mention the indignity of Black people being classified as three-fifths of a person.

The collateral damage was the creation of the Electoral College, whose votes are calculated by the number of representatives in the House and their two Senators. Like many constitutional scholars, Mystal spends a chapter explaining why he finds the Electoral College reprehensible, and sets forth in detail the inequity of the system that allowed George W. Bush and Donald Trump to win the presidency even though Al Gore and Hillary Clinton won the popular vote.

Mystal’s chapter on the Second Amendment is timely considering the recent decision of the United States Supreme Court, which found unconstitutional the provisions of a New York law that limited concealed carry to persons with a permit. Since 1913 applicants could obtain the required permit if they were able to show proper cause. This amounted to a demonstration of a special need for self-protection distinguishable from the general community. But the Supreme Court found that law too restrictive and a violation of a New Yorker’s Second Amendment rights. The result is that anyone in New York can have a concealed carry — no questions asked.

As Mystal points out in an argument that is not new, the reason for the Second Amendment is that Southerners were afraid of slave revolts. Afraid that the antislavery North would leave them high and dry if there was violence perpetrated by all those happy and contented slaves on their plantations, Southerners insisted on the ability to maintain a well-armed militia, in case someone like the not-yet-born Nat Turner or John Brown (both born in 1800) got any ideas. The result was the Second Amendment.

He goes on to make some good points about guns and gun ownership in America. For example, in the 1960s when the Black Panther party started arming themselves, Republicans like Ronald Reagan were quick to sign gun control legislation.

Mystal further asserts that our current interpretation of the Second Amendment was invented in the 1970s by the National Rifle Association. Originally the NRA was a relatively benign organization of people whose sole aim was to kill Bambi. But it morphed in the 1970s after a hostile takeover by white conservative Republicans. The newbies inculcated their fear of being unarmed or disarmed at the crucial moment when a gun could be used for self-defense — like George Zimmerman when he killed Trayvon Martin. Their fear of being unarmed is enough for them to overlook the ongoing national tragedy of mass shootings, suicides, violence against women and the lives of schoolchildren — “all so that they might feel a little less afraid when something goes bump in the night.”

In a sentence that sums up Mystal’s entire argument about guns in America, he argues that “Republicans will not make the killing stop, because they still think that near-unfettered access to guns is the only thing keeping them safe from Black people.”

Chapter Four — entitled Stop Frisking Me — deals with exception to the provision of the Fourth Amendment that prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. Under the stop-and-frisk doctrine, a police officer can do a pat-down search of a suspect for weapons for their own protection when the officer has a reasonable suspicion that a crime has been committed. Of course, if you are Black or brown, your chances of getting searched go up appreciably. They are called a Terry Stop — based on Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) and have become a tool of the police who manage to find all kinds of contraband when patting down a suspect for weapons.

Interestingly, the case originated right here in Cleveland. There’s a historical marker next to the Lakeside Courthouse marking the fact that the original case was tried in that building. The other significant aspect of the case is that when it was argued before the Supreme Court, both counsel for the prosecution, Reuben Payne, and counsel for the defense, Louis Stokes, were Black. It was a first for the high court. And even more meaningful was the fact that they argued the case before a court that included the first Black Supreme Court justice — Thurgood Marshall.

Every reader may not accept every argument asserted in this often revisionist interpretation of the Constitution. But it is interesting to consider another perspective of our constitutional history. White conservative Republicans are the villains throughout the book, so if you fit into one of those categories, this is probably not a book for your reading list.

But if you would like to walk in the shoes of a man who has been stopped several times for “driving while Black” or if you are interested in reading about how it feels to be Black, brown and poor trying to navigate the justice system in America, this book is worth the read.

Considering the court’s recent rulings overturning Roe v. Wade and the assertion by Justice Clarence Thomas that other landmark cases are open for re-interpretation, Mystal’s arguments ring true. Maybe it is time to do what several of my friends are investigating — immigration. Being an ex-pat can’t be that bad. And it may be better than living in a country where the darlings of the right, Clarence & Ginni Thomas, Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh decide your fate.

For those who are titillated by the arguments set forth by Elie Mystal, I would also recommend The Sum of Us – What Racism Cost Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together (One World Press, 2022). Author Heather McGhee has one theme, and that is that white people, Republicans and conservatives frequently vote and act against their own economic interest because of racism. The book is replete with examples of white voters and legislative bodies that shot themselves in the economic foot rather than share the American dream with people who do not look like them. McGhee’s writing style is a bit more complex than Mystal’s, but the read is well worth the effort.

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she serves on the Board of the Ohio History Connection, is currently vice president of the Cuyahoga County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission and past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.

2 Responses to “BOOK REVIEW: Reconsidering the Constitution in Black and White by C. Ellen Connally”

Mel Maurer

Thanks for calling attention to this author’s well reasoned views on our Constitution, seemingly with all of its built in prejudices. I’m not Black but I can relate to the issues raised. Mostly just common sense for some. I understnd the need for many compromises as it was written but not for correcting the problems they have created ever since.

Lucy M McKernan

Thank you for publishing this important article. I was not aware of the Thurgood Marshall connection to Cleveland with that historic “Terry” court case, and the marker outside the court house. I believe pro-gun advocates are just what you wrote: anti-Black. However, they play into the money-grubbing ones who profit most from the Pittman-Robertson excise tax, the 11% tax on every single weapon, ammunition, hunting permit, or piece of hunting equipment sold in America. (A disproportionate number of mass shooters in the U.S. are also hunters.) This money goes into a very large pool in Washington DC, and at the end of each fiscal year, gets doled back out to whichever states sell the most weapons and permits, usually park systems and benefactors other than whom the funds were originally earmarked for: victims of violent crime. Yes, it’s racism AND follow the money.