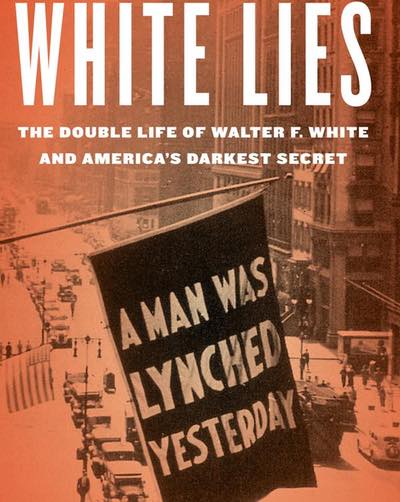

White Lies — The Double Life of Walter F. White and America’s Darkest Secret (Mariner Books, New York 2022) is the latest work by New York Times best selling author A. J. Baime. In the past, Baime has written about President Harry Truman, his accidental presidency and his unexpected victory in 1948.

In his newest work, Baime tells the story of Walter F. White, the executive secretary of the NAACP from 1929 to 1955. What makes the book unique is Baime’s ability to blend White’s life story with the tragic history of lynching in America. At the same time, he chronicles the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, the Harlem Renaissance and how a man who was one of the most prominent spokespersons for African Americans in the 1930s and 1940s has been seemingly swept into the dustbin of history.

Born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1893 to mixed race parents, White had blond hair and blue eyes. He was what many people in the Black community described as “light, bright and almost white.” But in his mind, body and soul, he was a Black man.

Part of White’s persona was the story that he often told of how he, as a 13 year old, and his father used shot guns to fend off members of a white mob who were about to attack his Atlanta home during the race riots of 1906. The problem with the account is that his older sisters deny its truthfulness — saying that their father never owned a gun. Whether the story is true or not, it set the pattern of White’s life and his lifelong struggle against racism and lynching.

In 1918, White accepted an offer to move to New York and work for the fledgling NAACP. At the time it had 76 branches, mostly on the East Coast, and only 8,490 members nationwide.

Thirteen days into the job, the NAACP was informed of a lynching in Tennessee. In an age before instant news feeds and cell phone cameras, there were only sketchy details available. The New York Times reported that a mob of more than 1,500 people had burned Jim McIlherron, “a negro,” at the stake after he was believed to have killed two white men.

White suggested that he travel south, assuming the identity of a white man, to get the details of the murder. Reluctantly, the officers of the NAACP agreed. He returned within a week with the graphic details of the lynching which were reported in The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP. The story spread around the county. This was the first of some 50 sojourns that White would make, posing as a white man, risking his life to learn not only facts about these vicious acts of mob brutality, but the mindset of the perpetrators. His bravery brought the ugly face of lynching into mainstream of American media.

In 1929 White became executive secretary of the NAACP. Under his leadership the NAACP became a significant national organization. He became a prominent member of Harlem society and hobnobbed with the leading literary figures of the Harlem Renaissance, often photographed with New York notables such as George Gershwin, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Paul Robeson and Sinclair Lewis, who traveled in his social circles. He was a mentor to the young Langston Hughes.

He was also the author of several books — becoming the first Black person to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. His book, Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Lynching, published in 1929, remains a classic. It is significant in that it debunked the “big lie” that lynching was a form of punishment of Black men who raped white women but instead found it was a form of white supremacy and vigilantism. This book also delivered a penetrating critique on southern culture that nourished this form of blood sport.

White dabbled in politics, although the NAACP is traditionally nonpartisan. His relationships with Democrats like New York’s Al Smith and FDR did much to cause Black Americans to sever their long-term allegiance to the Party of Lincoln. He became part of Eleanor Roosevelt’s inner circle. Republican Wendell Willkie was a close friend.

He claims to have facilitated Marion Anderson’s 1939 concert in front of the Lincoln Memorial, although others make the same claim. In 1946 he helped bring the blight of Isaac Woodard, a World War II veteran who was blinded by a South Carolina police, to Truman’s attention. This act of brutality against a veteran helped influence Truman’s decision to order the desegregation of the United States military. White persuaded Truman to speak to the NAACP Convention in 1947 — a first for presidential candidate of a major party.

Baime exposes the dark underside of the internal workings of the NAACP. In addition to financial troubles that sometimes prevented White and others from being paid, there were power struggles within the organization. W.E.B. DuBois, editor of The Crisis, comes across as self-centered and cantankerous as he sought to maintain his own niche and position of power. There are also capsule views of the significant events of the first half of the 20th century into which the NAACP was drawn, such as the Tulsa Race Riots and the trial of the Scottsboro Boys.

In this revisionist look at this now little-known American, Baime shows that White had faults. He was a chain-smoking, hard-drinking man whose marriage to Gladys Powell White, a mixed-race woman and would-be actress, suffered under the strain of his workaholic personality, frequent absences from home and lack of interest in his family.

Given White’s cozy relationship with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, Baime speculates that this relationship could only have occurred if White was feeding the FBI director information of some sort.

After 27 years of marriage, White divorced Gladys and married Poppy Cannon, a white woman that he was rumored to have had a long-term affair with. His marriage to Cannon in 1949, within weeks of his divorce, so angered his two adult children that they severed ties with him. His son went so far as to change his name.

White’s marriage to Cannon did not sit well with members of the Black community. It played into the stereotype that white supremacists had often argued — that Black men wanted to marry white women. His image was tarnished, and he fell from grace. He retired from the NAACP in 1955. Within months he was dead of a heart attack.

In his years as executive director, White grew the NAACP into a nationally known organization that was able to flex its muscle in many circles. Sadly, he was never able to obtain his decades-long dream of the passage of a federal anti-lynching law. In 2019, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act passed the House of Representatives by a vote of 410-4. But it was blocked in the Senate by Rand Paul of Kentucky. There remains to this day no federal anti-lynching law.

As the nation moved into the second half of the 20th century, White did not fit the image that Black America had created for itself. As Baime says in his epilogue, “White’s legacy faded into obscurity with remarkable speed. It was said that he was not Black enough for the new generation of civil rights fighters.” The preacher who led the Montgomery boycott, the students who sat in at southern lunch counters, these became the new faces of the Civil Rights Movement. But what Walter F. White did for the NAACP and his tireless fight against lynching should not be forgotten. Hopefully, historians will again recognize his contributions to the struggle for equality in America. White Lies will do much to achieve that goal.

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she serves on the Board of the Ohio History Connection, is currently vice president of the Cuyahoga County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission and past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.