This wasn’t my first rodeo; I’d been a “resident” of this same housing unit (more enlightened prison officials frown on calling them “cellblocks” in this day and age) in Ashland, Kentucky Federal Correctional Institution almost a decade prior, so I pretty much knew the routine. I still had a conman’s view of the world and knew that I soon would be attempting to find ways to make my 27-month stay at Club Fed as comfortable as possible.

Like they say, “It ain’t no fun when the rabbit got the gun.”

Most folks no doubt view doing time behind bars as being very egalitarian, with everyone wearing the same uniforms, for the most part eating the same food, and most of all, being governed by the same set of rules. But nothing could be further from the truth. Hierarchies are going to exist whenever two or more people gather together, and prison is no different.

The first hierarchy in the joint is established by what one is serving time for, and how much money was made off the activity that landed the person in prison. At the top of that pecking order in terms of respect were the genuine bank robbers — not some bozo who walks into the jug with a note in his hand (which, by the way, is shaking like a leaf), and his other hand jammed down in his pocket like he’s holding a gun, but is much more likely to be clutching a crack pipe. No, I’m talking about real, professional bank robbers, many of whom learned the trade from the fathers, no kidding.

Being a counterfeiter by profession back then — not someone who dabbled, but was a dedicated practitioner of the craft for decades — I was near the top of the human food chain when I arrived at the joint. And when people found out that Anthony “Tony Lib” Liberatore (the standup guy who once headed the Laborers’ Union in Cleveland back in the day) had sent a message for me to stop by the tailor shop (which was tucked inside the huge prison laundry) and see him as soon as I got settled in, soon I sitting down across from the man who was absolutely at the top — the Number One man — on the compound.

Liberatore, who had arrived on the compound a few months already prior, has the best job: Prison tailor. While he certainly didn’t need the money (for a number of years before his conviction he was considered by the FBI to be the head of the Cleveland Mafia), the guy who could alter prison threads and make them look at least a bit less “sad sack”-looking got paid big time by prisons standards.

Prison custom dictates that when someone arrives at the prison from your hometown, you check to see if they need anything: postage stamps, cigarettes, money on the books to go to commissary — whatever. Tony was more than gracious, and I passed it on to the next Clevelander.

Certain perks come along with being at or near the top in the eyes of the other convicts and they have to do with living arrangements. In society, but especially in prison, having personal space is critical to maintaining one’s sense of balance and well-being.

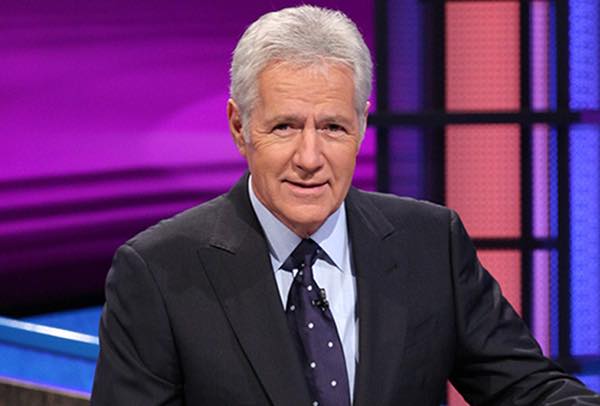

My second day on the compound I went into the TV room to play Jeopardy! By this point in my life I’d been in my share of lock-ups, jails and prisons, but one thing was common in all of them: At 7:30 the TV was going to get turned to Alex, and the other convicts didn’t care if your daughter’s wedding was being televised locally, sorry, Jeopardy! comes first. And that’s across the nation — or at least it was back in the day.

It wasn’t long before I was getting the stink-eye from a couple of the other vics that were swiftly becoming jealous with how quickly I answered the questions and even more impressed with my accuracy rate. Among the better educated prisoners, and some staff, Jeopardy! bordered on a religion behind bars, and I clearly was going to be the new Top Dog. The next night I damn near ran the board just to prove my first performance was no fluke. But standing in the doorway was a member of the prisons staff, the unit manager, a good ’ol boy named Ernie Barker.

Barker was unusual among staff members; he didn’t pay much attention to the unwritten rule that friendliness between staff and prisons was a no-no, and for good reason: Prisoners that cozied to staff were suspected of being snitches, and staff that got too friendly with convicts was considered weak by their superiors. But there’s exceptions to every rule, and he was one.

After I left the TV room Barker was standing near the door. “Impressive,” he deadpanned, which made me smile. “Yeah, I’ve been playing for awhile now,” I replied. We chatted for awhile (but we were right there out in the open so no one could make anything out of it) and he finished up by saying something I never forgot.

“You know,” Mr. Barker said, “If I got old and didn’t have no family to take care of me at home, I’d much rather be in a federal prison than a nursing home.” I thought for a moment, then realized he was dead accurate. Elder abuse simply doesn’t exist in federal prisons. But thank god, I’m surrounded by loving family as I slip into my dotage.

A few days later, a cell came open due to the occupants (who were a wonderful married couple — hey, prison don’t stop nothing!) both leaving on the same day. A few hours later I was told by one of the hacks that I was to change my cell.

Turns out that in spite of the fact some dudes had been in residence in the unit for months and a few for years (and no doubt thought they should get the privilege), I was being moved into the empty cell. Barker was back in the TV room the next day, and the day after that — and he turned out to be a very good player; we both looked forward to it each day.

But, and here’s where the respect comes in, in spite of the fact that I was sleeping in a two-man cell, I didn’t have a cellmate but once (and that was for a few days when the entire unit was on full) during the rest of my bid. For all means and purposes I had a single cell — which is as good as it gets in you’re doing time (as long as you are not on death row) — and it remained that way for the rest of my bid, thanks to Ernie Barker, but more so to Alex Trebek.

NOTE: Because of the solitude single-celling provided me, I was at last able to concentrate on what I’d been wanting to do for years: Learn to write. 18 months later my first book, From Behind the Wall was published in hardback.

2 Responses to “MANSFIELD: How Alex Trebek Made My Last Bid Easier”

Peter Lawson Jones

Great essay, Mansfield. Do you know what happened to Ernie Barker? Did you ever consider auditioning for Jeopardy? BTW, my first appearance on national television was a game show in the summer of ’79. Won some money, but would’ve won even more had one of my teammates concurred with my answer in the game’s final round.

Kathy Wray Coleman

Great write up Mansfield