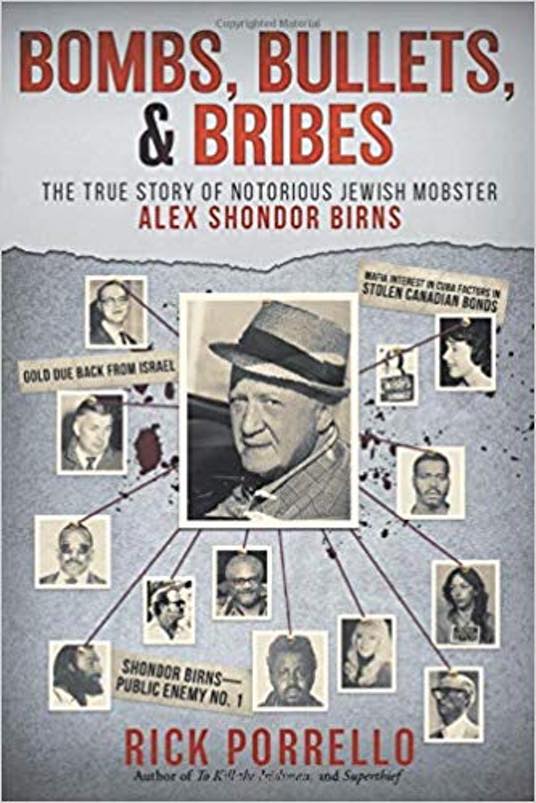

Bombs, Bullets, & Bribes: The True Story of Notorious Jewish Gangster Alex Shondor Birns

By Rick Porrello

Reading parts of Rick Porrello’s captivating biography of perhaps Cleveland’s most notorious and colorful numbers gangster, Shondor Birns, was akin to a walk down memory lane for me.

From the very first pages, with Shondor’s upbringing in the rough-and-tumble Woodland and 55th Street neighborhood (not many blocks from where I was born some 30 years later), to attending the same elementary and high school, I could identify many of the places mentioned in the book since they were still in existence when I hit the streets of Cleveland in the early ’60s.

Right from the beginning of the book, Porello in an author’s note explains that while he wasn’t present during many of the conversations he recreates for the book, he attempted to stay true to the argot; and since this was the language I grew up with I can attest to the fact that he captured the “feel” of the underworld characters he writes about so very well.

Birns was a numbers operator, the criminal enterprise of illegal lotteries, something that has been going on probably ever since man learned how to count, and more importantly, learned how to take financial advantage of his fellow man. My father “booked” the numbers in the tavern that we lived above on 31st and Scovill Avenue, and where I was virtually raised. After age three I spent every waking minute I could following my father around in his beer joint. At first, my mother balked, but eventually, she got used to me being “downstairs.” It was quite an education.

What made Birns such a legend was the fact he was a Jewish mobster successfully operating in the largely black world of the numbers. He employed the “runners” who collected the bets people like my father who owned businesses “booked.” They took the money and betting slips to the houses where the tallying took place, and brought back the payoffs to the people who occasionally “hit,” meaning they won— the payoff being as high as 600-to-1 tax-free dollars.

Virtually everyone — even the church-going people — played, and most with daily regularity, so the “take” for the operator was huge. And the risk was small since every beat cop got his “gapper” at the end of the week which meant that rarely did anyone go to jail, that is, until the bombs started blowing up under cars in the ’70s.

In 1962, when Birns was probably at the height of his wealth and power, almost straight out of high school (and already married) I got a job at the old Illuminating Co. It wasn’t long before the sharp-dressing Italian dude who owned the company that installed the coin-operated machines (the jukebox, pinball, and shuffleboard) in our tavern stepped to me with a proposition. He was always on the lookout for someone who worked at places where there were lots of employees, such as steel mills and auto plants, and yes, the light company.

Pornography was still illegal at the time and the Italian dude (of course I recall his name, but since I still enjoy breathing, it will remain my secret since, yes, he was part of the mafia and they do have long memories) had an offer for me that I really didn’t want to refuse. He could sell me a pack of 10 different 8mm, 15-minute porn films for $200; I could, in turn, sell one of the more popular titles for $150. You do the math. I even bought one of those Bell & Howell Regent home movie projectors, and my straight-laced wife served drinks in our basement when we hosted viewing parties where we’d always sell out of films. I’d just turned 22 years old.

My guy would drop the packages off at the tavern whenever he got the time, but if I was in a rush for them (which I always was since they were selling like hotcakes), I could go down to the mobster hangout, the Theatrical Grill on Short Vincent, where he spent a lot of his time. As soon as I walked in and got his attention (they really weren’t too keen on black dudes in the club, unless they had a mop and bucket), he’d quickly take me out to the trunk of his car, which always must have had over 100 of the packages of films.

That’s where I first saw Shondor Birns.

Birns had his own table at the Theatrical and must have had one at many other gangster hangouts around town, as I later learned. He greeted everyone cordially, even a 20-year-old black kid like yours truly. Of course it could have been the clothes, since I was as sharp a dresser as any of the gangsters (hell, I could afford it!), or it could have been the fact that whenever I walked in, my Italian friend got up and walked out. Shondor, like everyone else in the club, knew what I was there for. It was a great little hustle, and the police weren’t the least bit interested in what we were doing, meaning there was no payoff, we got to keep all of the loot.

While my guy was always super cool, Birns was a completely different kind of dude. Whereas the Italian mobsters mainly hung out down at the Theatrical or on Murray Hill in Little Italy, I’d see Birns uptown too, at the black clubs and after-hours joints around E. 105 and Euclid. He was just as comfortable, well-known, and well-liked in those haunts as he was downtown. He always kept a fat bankroll, tipped really big, and had a real thing for attractive, buxom black women.

An older cousin of mine, “Sonny Man” Johnson, was one of Birns’ top lieutenants, and once, in one of the “black and tan” clubs where the races mingled intimately, the Merry Widow on E.105, he saw me come in and invited me over to the table where he was sitting with Birns and another man. At age 21, there I was, drinking with gangster royalty.

As the ’ol boy said, “I was shittin’ in high cotton.” Once he saw who my cousin was, Birns even got me a better wholesale price on the films, since my gut instinct tells me he had a piece of the action all along. But I didn’t know and didn’t want to know.

Sure, it’s not politically correct these days to glorify gangsters, but how was Birns any different from the CEOs of corporations that pollute the air and water? Here’s the difference: They went to Harvard, Yale, or some other Ivy League school and should have known the damage they were (and are) doing to the environment and the planet for money.

Whereas Birns, like me, only went to the school of hard knocks and provided people with happy — albeit, illegal — distractions. You can’t knock someone for being a hustler in this country — hustling is as American as apple pie. We weren’t hurting anyone but since we didn’t come from money we were supposed to stay poor, right?

So, in the end, who are the bigger criminals?

From CoolCleveland correspondent Mansfield B. Frazier mansfieldfATgmail.com. Frazier’s From Behind The Wall: Commentary on Crime, Punishment, Race and the Underclass by a Prison Inmate is available in hardback. Snag your copy and have it signed by the author at http://NeighborhoodSolutionsIn