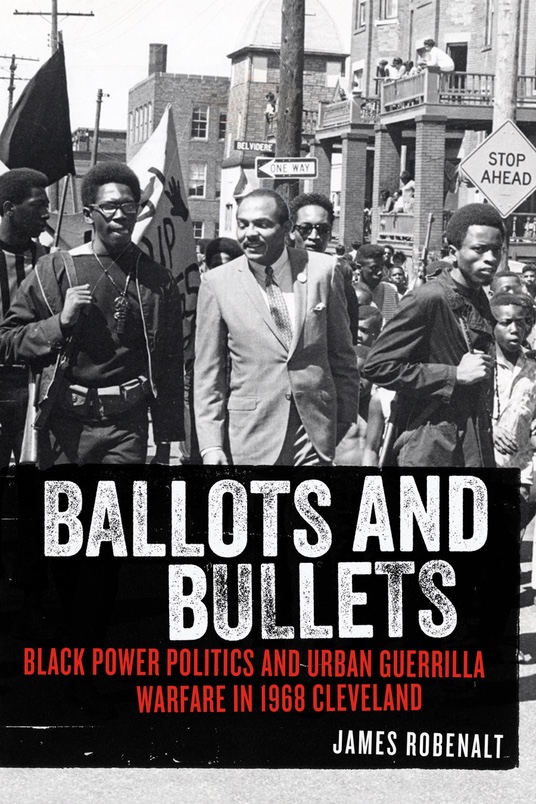

Ballots and Bullets — Black Power Politics and Urban Guerra Warfare in Cleveland in 1968 by James D. Robenault

Cleveland lawyer and historian James D. Robenalt has tackled a wide variety of topics in his literary career. Starting with two books on Ohio political history in the early 20th century, he moved on to become a noted authority on the Nixon Administration and the Watergate scandal. Partnering with former White House counsel John Dean, he is a frequent lecturer and television analyst on Watergate and Nixon. In 2015 he authored January 1973 – Watergate, Roe V. Wade, Vietnam, and the Month that Changed America Forever.

In his newest book Ballots and Bullets – Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland, he focuses on events that transpired in Cleveland’s Glenville neighborhood in late July 1968. Traditional accounts of the events discuss the tragic death of three police officers, three citizens described as black nationalists, and one bystander. There were also injuries sustained by 15 other people that included police, nationalists and bystanders. When the neighborhood went up in flames, there were massive property losses. A community was forever changed. Cleveland made national headlines in a year in which the nation was engaging a hopeless war in Southeast Asia and wept after the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy.

In his reexamination of the events in Cleveland, Robenalt delves deeper than the deaths and resulting turmoil and looks at race relations, policing, black power and urban violence in America during the 1960s and specifically in Cleveland. The story is not just of urban violence in Cleveland but is a reexamination of the problems that faced the nation in the 1960s.

A key element of the story is the 1968 election of Mayor Carl B. Stokes and how his role as a black mayor affected the city and its population during this tense time in Cleveland’s history. Stokes appears on the cover of the book walking in a parade commemorating the revival of the Hough neighborhood after the riots that had occurred two years earlier. His appearance at the event was representative of his unique relationship with the nationalist community.

Stokes came to power in November 1967 through a fragile alliance of blacks and liberal whites. This loose coalition always had Stokes walking a thin line to maintain his political base. But as Stokes biographer Leonard Moore says, Stokes “made it clear to the nationalists that they represented an essential part of his constituency and their support was critical to his success.”

On the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April of 1968, Cleveland was the only major city in the nation that did not go up in flames. This was attributed to the actions of Stokes, who, along with other black leaders, walked the streets of Cleveland and maintained calm. Suddenly, many in the white community nationwide saw Stokes as the person to fill the void left by the death of King. There was speculation that Stokes would run for vice president with Hubert Humphrey in the upcoming presidential election. His political star was on the ascendency.

Upon taking office Stokes faced the challenges of every mayor of a major urban area — an aging infrastructure and housing stock, unemployment and lack of business opportunities. Cleveland also faced major issues regarding segregated schools — the result of years of segregated neighborhoods. By the early 1960s there were many demonstrations against the building of new schools in black neighborhoods that black residents argued would only perpetuate segregation. One such demonstration in 1964 resulted in the death of a white minister who was run over by a bulldozer as he attempted to block a construction site. An attempt to have black students attend classes at a school in the largely Italian Murray Hill area brought out the worse in some citizens. Racial tensions were high.

President Lyndon Johnson attempted to cure the ills of urban America through his War on Poverty. He proposed to end poverty through the massive influx of social programs and urban renewal. Thinking in the same vein, Stokes came up with the idea of Cleveland Now — a hastily organized, large-scale urban redevelopment and jobs training program that supposedly would rejuvenate Cleveland. Once again Stokes was recognized nationally for this innovative program.

But in its haste to initiate Cleveland Now and get the program started, the Stokes administration determined that all distributions of funds would be under the mayor’s control. Funds did not have to go through the city council. Unfortunately, there were few checks and balances whereby recipients were vetted and made accountable.

Among the many distributions of funds was an allocation to Fred Ahmed Evans and his African Culture Shop. Evans, who identified himself as a black nationalist and community activist, had been an early Stokes supporter. On paper his program appeared to provide positive programs for black youths. But when the dust settled after the urban violence of July 1968, it was determined that Evans was at the center of the controversy, and portions of the funds given the cultural center by Cleveland Now were spent to purchase the weapons used in the shootout.

In addition, when the violence commenced, Stokes ordered white police officers out of the neighborhood and allowed only black officers to patrol the streets. This decision outraged most white police officers. It was the beginning of the end of Stokes’ honeymoon with the Cleveland police, many white voters and segments of the black community. Stokes’ ascendency in local and national politics began to ebb.

Cuban revolutionary Che Guevarra is famously quoted for saying “one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter.” That is the perspective that Robenalt takes as he looks at both sides of what happened on July 23, 1968 in Cleveland. Using newly discovered original sources, FBI records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, court records and personal interviews, he brings a new perspective to the events leading up to the nights in question, the criminal prosecutions that followed and the racial politics of Cleveland.

The early chapters of the book give the reader a tutorial on the rise of the black nationalist movement in America. It explains the frustration of many blacks, which was brought about by generations of inequality. Incidents cited in the book of illegal conduct by white police officers only buttress the frustration experienced by black citizens.

In a meaningful summary, Robenalt concludes by showing how the events of July 1968 changed Cleveland and its political landscape for a decade.

Longtime residents of Cleveland will have an opportunity to reflect and reassess this critical period in the city’s history in light of these revelations, the passage of time and Robenalt’s insightful reexamination of the facts. Readers who are new to the subject will be fascinated by this new look at Cleveland’s past and will gain meaningful insights into life in urban America during the 1960s.

Ballots and Bullets – Black Power and Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland is set for release in July. It is available for pre-order on Amazon.com.

C. Ellen Connally is a retired Cleveland Municipal Court judge. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she serves on the board of the Ohio History Connection, is currently vice president of the Cuyahoga County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission and treasurer of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation from a PhD from the University of Akron.