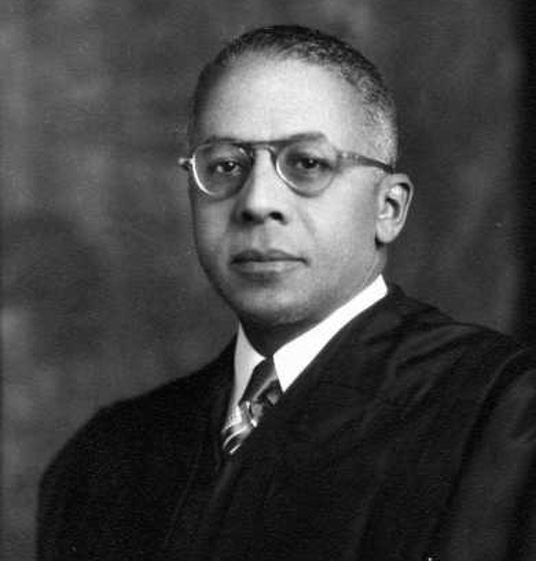

When Governor John W. Bricker appointed Perry Brooks Jackson to a seat on the Cleveland Municipal Court in 1942, the judiciary in Ohio was forever changed. The Honorable Perry Brooks Jackson had become the first black judge in Ohio, joining only a handful of other black judges across this nation. The story of Jackson’s life and judicial career is told with familial devotion by his nieces, Anita P. Jackson and Laureen B. Beach, in the newly published work In The Service of Community and Honored Elder – The Honorable Perry B. Jackson, published by New Concord Press.

Born in Zanesville, Ohio in 1896, it is significant that the year of Jackson’s birth coincides with the United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. That decision upheld state laws requiring racial segregation in public facilities under the doctrine of “separate but equal” and set the tone for race relations until well into the 1960s – a transformation that Jackson would live to see.

While segregated schools were the norm in most of America in the first decades of the 20th century, such was not the case in Zanesville. Jackson attended integrated schools where he excelled. Even though the schools may have been integrated, life in Zanesville was not always one of racial harmony. The young Perry was subjected to incidents of racial discrimination that left a lasting impression on him, but did not deter his determination to achieve.

Imbued by his family with a strong work ethic, he would eventually come to Cleveland and work his way through Western Reserve University (now Case Western Reserve University) where he graduated magna cum laude in 1919. He went on to graduate from Western Reserve Law School in 1922.

While most new lawyers in the 1920s struggled to get started in the practice of law, the challenge was particularly difficult for black lawyers. There were no black law firms in Cleveland to offer a new lawyer employment, and white firms would hardly consider a black associate. So with less than one dollar to his name, Jackson started out on his own.

Realizing that he would have to engage in other business activities to support himself, in 1923 Jackson started working for The Cleveland Call, the city’s black newspaper. He worked up to the position of editor and left the position in 1927 when the paper merged with the Cleveland Post to become The Cleveland Call and Post.

He went on to serve in the Ohio General Assembly and on Cleveland City Council, all groundbreaking positions for a black man in the 1920s and 30s. Beginning in 1934, Jackson was employed as an assistant city prosecutor for the City of Cleveland, another first for a black lawyer. He left the office in 1941 as the chief police prosecutor – yet another first.

Jackson always used his personal charm, gentlemanly manner and commitment to his community to help himself along his career path. By what today would be called networking, his involvement in numerous civic, religious, fraternal and philanthropic organizations brought him to the attention of many influential people in Cleveland. He was a devoted member of the Republican party – an affiliation that also helped to advance his career.

His story and that of his loving wife Fern, whom he married in 1933, is very much the story of black life in Cleveland in the first half of the 20th century. Long-time Cleveland residents will recognize the names of numerous Cleveland businesses and civic leaders of years gone by — institutions and people whose contribution to Cleveland are often lost to younger generations.

Like the discrimination that Jackson suffered in Zanesville as a young person, there were also acts of bigotry in Cleveland. One such incident happened in 1935. Jackson attended a luncheon meeting for a committee of the Cuyahoga County Bar Association at the Hollenden Hotel. When the meeting started, the head waiter approached the chairman and stated that “Negroes” would not be served. The entire committee left the establishment in protest. Later that year, represented by Chester K. Gillespie, the dean of Cleveland’s black lawyers, Jackson sued the hotel and recovered $300 – about $5,000 in 2016 dollars. Ironically in 1952 and 1966 Jackson was honored at events held at that same establishment.

The story of Perry B. Jackson is a lesson in the history of African-American life during the 20th century. He would eventually move from the municipal court to judge of the Cuyahoga County Domestic Relations Court – the last black judge to serve on that Court – and end his career on the General Division of the Common Pleas Court, where he served with distinction as one of the most respected judges on the bench. His election to the Domestic Relations Court in 1960 marked the first time that a black person would be elected to a countywide office in Cuyahoga County.

Having reached the mandatory retirement age for judges when his term ended in 1972, Jackson had no inclination to give up his judicial robe. He was appointed by the Ohio Supreme Court to serve as a visiting judge on the Common Pleas Court where he served until 1986, continuing to mete out justice with the same even hand and the same judicial temperament that exemplified his judicial career from his first day on the bench in 1942.

During his long career Jackson was able to live to see the “separate by equal” doctrine struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1954 decision of Brown v. Board of Education. He saw other blacks ascend to the bench including his fellow Republican, Judge Lillian W. Burke, who became the first black woman judge in Ohio in 1969. He would live to see the appointment of Thurgood Marshall to the United States Supreme Court in 1967, something that would have been unheard of at the time of his birth.

If he were alive, the Honorable Perry B. Jackson would proudly smile, counting the achievements of black lawyers in Cleveland and the number of black judges who sit on our municipal, state and federal courts in Ohio, knowing that he was the trailblazer who opened the door for each one of them. And his legacy lives on as each one dons his or her robes to take the bench each day.

In The Service of Community an Honored Elder – The Honorable Perry Brooks Jackson by Anita P. Jackson, Ph.D. and Laureen B. Beach, M.Ed. is an attempt to explain and explore the legacy of a great man and trailblazer. It is a significant contribution to the history of Cleveland’s black community and a wonderful reflection of the history of the judiciary in Cleveland.

Available on Amazon.com and also at perrybjackson.wordpress.com

C. Ellen Connally is a retired judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. From 2010 to 2014 she served as the President of the Cuyahoga County Council. An avid reader and student of American history, she serves on the Board of the Ohio History Connection and was recently appointed to the Soldiers and Sailors Monument Commission. She holds degrees from BGSU, CSU and is all but dissertation for a PhD from the University of Akron.