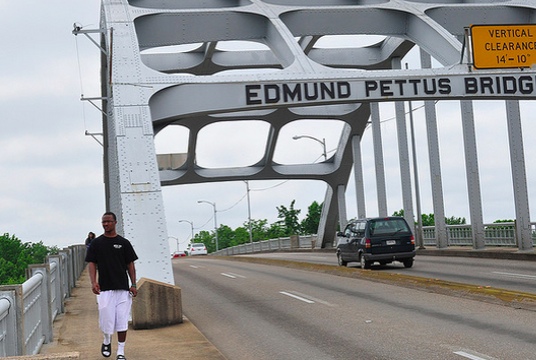

March 7, 1965 — a day now widely known as “Bloody Sunday” — dramatically changed the Civil Rights Movement, and irrevocably altered my life in the process. Now-Congressman John Lewis attempted to lead a group of 600 civil rights activists on a protest march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, determined to head for the state capital in Montgomery 55 miles away to demand that blacks be given the right to register to vote without hindrance.

The marchers were hooted at along the way by mobs of white racists, and met at the bridge by an armed contingent, comprised of local and state law enforcement (many of whom were Klansmen by night) that were determined to stop the march — no matter how much brute force they had to employ. The ensuing carnage, captured by national TV cameras, awakened the conscience of the nation.

I was supposed to be in that march, but, alas, I was not … and the fact that I wasn’t altered and shaped my life in ways I couldn’t begin to imagine at the time.

* * *

I’d married much too young at age 17 and left home with a wife and baby at age 18. Straight out of high school I landed a “good” job working at the Illuminating Co., starting off as a helper in the skilled crafts shops working among carpenters, painters, machinists, welders and blacksmiths. By age 21 Lenny Jurosik — a grizzled, 60-something-year-old blacksmith who was a freethinker and probably was a socialist … that is if he hewed to any political affiliation — had opened my eyes and radicalized me.

Part of my job duties were to help him steady larger pieces of steel as they came out of the forge, heated to a cherry red, ready to be hammered and bent into various shapes and forms. The other shop helpers avoided helping Lenny whenever they could due to the intense heat generated by the oxygen-driven forge, but I was thirsty for the knowledge he imparted to me about the properties of steel, but more importantly I was thirsty for the knowledge about life he was imparting to me.

Lenny was a real-life activist/philosopher … the first one I’d ever met. And when, he saw that I was intently listening to him and the wisdom he was sharing, he suggested some books for me to read; books I eagerly obtained from the library and devoured. It was from the enlightenment I gleaned from those pages, and Lenny’s willingness to explain and debate the finer points of the information, that I began my journey into true manhood … to become a sentient, thinking, human being.

I was almost ashamed of my lack of education and awareness … that an aging white man of Eastern European descent had to explain to me my own history and the reason for the dire circumstance of my race. When I once mentioned this, Lenny laughingly explained that it was no accident that I had been mis-educated — that it was by design … a method of insuring that I (and others like me) would forever be a wage slave.

He eventually suggested that I read the works of Carter G. Woodson, who is credited with starting Black History Month. Woodson wrote:

“If you can control a man’s thinking, you don’t have to worry about his actions. If you can determine what a man thinks you do not have to worry about what he will do. If you can make a man believe that he is inferior, you don’t have to compel him to seek an inferior status, he will do so without being told and if you can make a man believe that he is justly an outcast, you don’t have to order him to the back door, he will go to the back door on his own and if there is no back door, the very nature of the man will demand that you build one.”

When I eagerly reread that passage to Lenny, he, in the manner of an ancient master, simply smiled slightly, gently nodded his head in the direction of his student, and latched upon me with his fierce dark eyes. It was as if he was saying, “So, now you know.”

* * *

In early February of 1965, a coworker, whose parents were deeply involved in the movement for black justice, informed me that he was taking vacation time to go to Selma to join the upcoming march. I, now freshly awakened, decided that I too wanted to go.

However, when I mentioned it to my wife, Christine, she, as if telling a child that he couldn’t go out and ride his bike, said “no.” I, of course, pouted, and when I again broached the subject a few days later she, treating me as if I had said I wanted to run off to join the circus, or apply for astronaut training, dismissively restated her decision with a finality that clearly said, “And don’t ever raise this subject again!”

And she had a comrade in her decision: My mother. Although the two of them were like oil and water, barely managing to be civil in each other’s presence, they closed rank on this issue. My mother, being raised in the South, still retaining vivid memories of white-robed Klansmen terrorizing her Louisiana neighborhood, was fearful for my safety, while Christine was no doubt more concerned with someone damaging her meal ticket.

If dictionaries had included the word “pussy-whupped” (most people spell the word “whipped” but when it was as bad as it was in my case, it was “whupped) my sad, cowardly visage would have adorned the insertion. I truly had been a little boy who married a 17-year-old grown woman … who actually was going on 40 at the time of our union.

Needless to say, I didn’t go.

But when I saw the heroic deeds being done by young people on the bridge a few weeks later I was deeply ashamed of my cowardice. And with every additional step of the civil rights struggle I became more agitated, more emboldened to claim my manhood by renegotiating the terms of my marriage, but was being rebuffed at every turn by Christine who virtually said, “I’ve been running things around here for this long, and see no reason to change, so why don’t you just go back to sleep little boy.”

And, as God is my witness, I tried to go back to sleep, but I couldn’t.

As Elton John was singing:

“But how can you stay, when your heart says no

How can you stop when your feet say go …”

It took a number of years (filled with a couple of failed attempts at marriage counseling, the last counselor whispering to me as we were leaving his office “You have to leave, it will never work”) before I found the courage to do the hardest thing I’d ever done in my life up to that point: Leave my family and the security we had worked so diligently to establish.

But by the time I found the courage to leave, the Civil Rights Movement was stalling and I felt I had missed out on my chance to do something important for my race. That’s when I dropped out and became an outlaw — which is far different from a criminal. I merely wanted nothing to do with laws that I felt didn’t respect me, so I was determined to live “outside the law.”

Of course, when money ran out I became a criminal, and spent close to the next three decades living the highlife of a libertine, pursuing … I don’t know what. But my conscience never quit kicking my ass.

When I finally came to my senses while in prison at age 50, I began to work demonically to try to make up for those lost years, those years I should have spent fighting battles to improve the conditions of the underclass of my race.

The events that occurred 50 years ago on the Edmund Pettus Bridge caused me to embark on my journey to manhood, and still, to this day, inspires, informs, and gives a sense of direction and purpose to my writing, civic engagement and occasional hell raising.

Oh, and thanks Lenny, from the bottom of my heart.

[Photo: Social_Stratification]

From Cool Cleveland correspondent Mansfield B. Frazier mansfieldfATgmail.com. Frazier’s From Behind The Wall: Commentary on Crime, Punishment, Race and the Underclass by a Prison Inmate is available again in hardback. Snag your copy and have it signed by the author by visiting http://NeighborhoodSolutionsInc.com.

From Cool Cleveland correspondent Mansfield B. Frazier mansfieldfATgmail.com. Frazier’s From Behind The Wall: Commentary on Crime, Punishment, Race and the Underclass by a Prison Inmate is available again in hardback. Snag your copy and have it signed by the author by visiting http://NeighborhoodSolutionsInc.com.