Whenever I go to Quicken Loans Arena to cover a Cavaliers’ game, I invariably stop to talk politics with one of the workers who tend to the VIP lounge on the ground floor.

A dapper and impeccably mannered black man around 60 or so, he and I have been chatting for years and I have always been impressed with his calm, astute insights and measured analysis regarding the local political scene. Lately, however, he’s been anything but calm and measured – he’s been on fire.

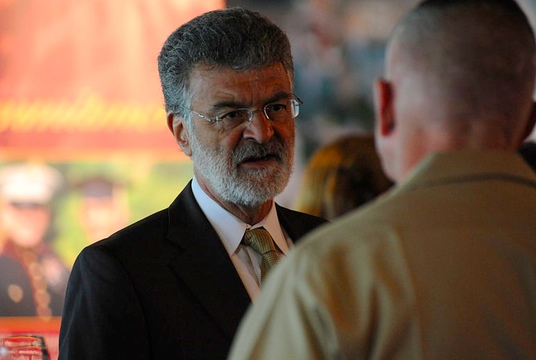

The subject of his growing discontent is Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson, a man he has faithfully backed for the past 25 years but whose unflinching support of the Cleveland police in the face of the Department of Justice’s attempt to make major changes in the local safety forces has been something my friend simply cannot stomach.

And he’s not alone in his viewpoint. In my conversations with African-American political activists, I sense that there is a palpable feeling in the black community that Jackson has profoundly betrayed them with his defiant defense of the police. This is not simply a nuanced debate about political priorities. This is visceral – and it’s not going away.

The problem for Jackson is that it appears – despite his impressive electoral record – that his true support is a mile wide and an inch deep. He has never been a rallying force among voters, nor has he won any life-or-death battles with political foes or corporate interests. Like Old Man River, he has just kept rolling along. That is, until now.

In the great political movie The Last Hurrah, a long-time, big city mayor gears up for one last run for office in the late 1950s, a time when the old-time machine politicos had to either adapt to the changing times or fade into oblivion.

Jackson’s Last Hurrah will take place over the next several months, when he’ll have to finesse his way around either the removal of his two safety- forces albatrosses, Michael McGrath and Martin Flask, or explain why he chooses to keep them on in the face of scorching criticism from the black community and a possible recall.

Of course it doesn’t help the mayor that pugnacious Cleveland police union head Steve Loomis has adjoined himself to Jackson’s hip by saying that if the two of them chose to fight the Feds on the DOJ’s investigation “we could kick their ass.”

Loomis is also known for simplistic statements, like, “if people do exactly what we tell them to do, no one will get hurt,” (Note: Perhaps “yes, mein kommandant” would be the preferred response.) He’s also given to perpetual whining about how tough the job is and how many of his officers are apprehensive about going to work. (Note: If the job is too hard for them and they wake up skittish every morning, maybe it’s time for career counseling.)

My guess is that the last thing members of the black community want to see is Jackson teaming up with Loomis to battle with the Feds in order to thwart attempts to reform the police department and curb the use of excessive and deadly force.

Throughout his political career, Jackson has been known for being slow and steady – a grinder who flies under the radar most of the time. That approach will not work in this case. Jackson has to act boldly and decisively while under white-hot scrutiny by both the media and his constituents. If not, slow and steady will end up . . . going, going, gone.

Just a few months ago there was talk of Jackson running for a fourth term in 2017 and that no one could beat him. Now, that seems out of the question. Even if McGrath and Flask resign and Frank comes out relatively unscathed in his consent-decree battle with the Feds, the damage has already been done and his legacy has been permanently tainted by the fair or unfair tag of “police apologist.”

At this point, Frank’s Last Hurrah is not about winning. It’s about rescuing a career whose defining moment in many people’s eyes will always be that– just when the Feds had the Cleveland police in their crosshairs – Jackson was not there when the black community needed him the most.

Larry Durstin is an independent journalist who has covered politics and sports for a variety of publications and websites over the past 20 years. He was the founding editor of the Cleveland Tab and an associate editor at the Cleveland Free Times. Durstin has won 12 Ohio Excellence in Journalism awards, including six first places in six different writing categories. He is the author of the novel The Morning After John Lennon Was Shot. LarryDurstinATyahoo.com

Larry Durstin is an independent journalist who has covered politics and sports for a variety of publications and websites over the past 20 years. He was the founding editor of the Cleveland Tab and an associate editor at the Cleveland Free Times. Durstin has won 12 Ohio Excellence in Journalism awards, including six first places in six different writing categories. He is the author of the novel The Morning After John Lennon Was Shot. LarryDurstinATyahoo.com