By Roldo Bartimole

The political mess New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie put himself in made me think back to political crises involving two Cleveland mayors and how they handled their emergencies.

Dennis Kucinich made the muddle he experienced into a defining moment. It revealed, as Christie’s did, character flaws already noticed by the public. It was all unnecessary and damaging.

They provide pieces of Cleveland mayoral history of how to handle a crisis and how not to.

Kucinich’s test involved a dramatic move he made by hiring Richard Hongisto from San Francisco. Hongisto had been charismatic police chief. He was considered a lefty who would fit the Kucinich’s regime. And maybe help control the testy Cleveland police. The force often became a mayor’s major headache.

In a possible telling sign of what would come I was told that in an interview at the time with Tom Hayden, a long time peace and justice activist in San Francisco, asked chief Kucinich advisor about the administration’s ability to govern after winning the office. The reply was “the ability to win is the ability to govern.”

This sentiment proved the seed of the administration’s demise.

The news media, as usual, played a leading and distorting role in a tussle between the administration and Hongisto.

It appeared that Hongisto, a strong personality, got more publicity than the administration desired. Even police sided with him to Kucinich’s ire.

Difficulties reached a crisis point when Hongisto complained of interference in vice squad changes and in the carnival corruption case involving Council President George Forbes. He blamed some in the administration.

Hongisto, as a result, apparently felt his job in jeopardy. He talked with community people apparently seeking support for a contract for the job he held. These rumors leaked to the media.

As it evolved, the Plain Dealer ran a piece that was headlined “Kucinich tells Hongisto to resign.” Both denied it. Hongisto claimed no “basis” for the charge other than rumor.

But things began to escalate.

In those days there was real news competition. The Press followed with a story. It said Hongisto had been pressured to commit “unethical” acts.

The Kucinich people were caught off guard by these stories. They apparently felt sandbagged by Hongisto. He was seen becoming locally popular by riding out with his police officers. He got too much notoriety for Dennis to tolerate.

This accelerated the sour events.

Kucinich and his close and very loyal band made public errors. They escalated the situation.

Kucinich and Hongisto met privately at City Hall. As the meeting ended Hongisto walked out to the elevator just outside the mayor’s office. He was bushwhacked by a gang of reporters. An unexpected “press conference” ensued as the door was kept open. Hongisto inside was forced to engage the hoard. Within minutes, Kucinich appeared. I remember him saying to Hongisto, “Let’s settle this thing now.” Public confrontation was ensured as media people followed the mayor and Hongisto.

High drama ensued before a room full of reporters, cameras and tape recorders. It made for circus media. It was the last way to deal with a political crisis that required privacy.

Kucinich obviously had decided to take the initiative. He demanded Hongisto provide details of the criticisms of unethical behavior. As Gen. Benjamin Davis did with Carl Stokes (below), Hongisto refused.

They returned to Red Room where most official meetings with the mayor, public and press take place. The stage set for disaster. And that’s what happened.

Here’s what I wrote in April, 1978:

“Hongisto effectively refused to accommodate. He refused to name names or events but, unlike Davis who said he would never respond, Hongisto promised that after reviewing evidence he had at his office he would respond.” He maintained cool; Dennis heated.

Now it was Kucinich’s move.

Kucinich acted, unfortunately for him, before TV cameras. Instead of calling Hongisto to his private office he threatened and then suspended the chief. With cameras rolling, Kucinich gave Hongisto 24 hours to produce evidence of his ill-defined charges. Kucinich said Hongisto could use his office but assigned his loyal safety director to watch over him. It seemed excessive. The monitoring became TV news and produced front page photos. The PD labeled it “house arrest.” TV news gave live coverage and half-hour specials. It smacked of totalitarian excess.

I wrote at the time:

“If Kucinich had known that the chief had so little documentable evidence he could have allowed Hongisto free access to the office. He apparently feared more damaging evidence from Hongisto, who mentioned but never produce tapes.”

Kucinich insured high drama by calling a press conference late the next afternoon with all three major stations going live. High drama. Hongisto was to appear at 5:30 but didn’t. Kucinich fired him on live TV.

Hongisto played his role perfectly. He arrived at city hall after the fireworks.

Here’s how I described it:

“About 8 p.m., reporters, tired and hungry, moved downstairs to the front of City Hall. Shortly thereafter two figures slowly walked down a dark, wet East 6th Street toward Lakeside and City Hall.” “They’re they are,” someone yelled.

“A movie script could not have set the scene more dramatically as reporter started down the wet City Hall steps toward the Hongistos, Elizabeth and Richard.” (Although they dramatically walked down to city hall in the rain, a car was there later to whisk them away.)

By that time on Good Friday, Hongisto knew he had been fired. He played the martyr role well, shifting his charges to a direct attack on Kucinich and his administration.

He addressed reporters:

“You know it’s very strange to be asked to come here as a reformer, to show up as a reformer, and then to start reforming and then to get into trouble for it,” he told reporters. “I thought that I was supposed to be one of the good guys but we found out that the good guys were getting fired.”

He charged, as did others, that people in the administration were abused, chronically so, he said. It was an image of Kucinich taking root.

What was clear, however, was that Kucinich handled his crisis in the worse way possible. He died in 2004.

It was always my read that the young Kucinich was too influenced by Bob Weisman. I remember after my newsletter went public, I ran into Sandy Kucinich, Dennis’s wife. We stood at the balcony on the second floor near the entrance to the Mayor’s office. Since the double issue on the Hongisto event was tough on Dennis I expected a cold reception. Instead, I felt her response was most sympathetic. I believe she resented the strange hold Weismann had on her husband as these events suggested. She seemed to be saying, continue to be critical.

(I always thought that Weismann helped elect four successive Cleveland mayors. He directed Dennis, a Democrat, to back Republican Ralph Perk who won election. Then he and Dennis took Perk down, making Dennis mayor. Weismann’s doctrinaire hold on Dennis damaged him and he was toppled, electing Voinovich. I have no evidence but I believe Weismann advised Mike White as he defeated George Forbes. The only support for this thought was that White, after taking office, strangely nominated Weismann to the county port authority. An unexpected political reward. Weisman was the last person business people wanted at the port. Council rejected Weismann. However, White, I can only speculate, fulfilled a political debt.)

Unfortunately for Dennis the Hongisto affair along with other problems resulted in a recall. It failed. However, the nature of his behavior, much as we see with Gov. Christie, was character revealing. Dennis did bounce back and he has a national reputation beyond his Cleveland legacy.

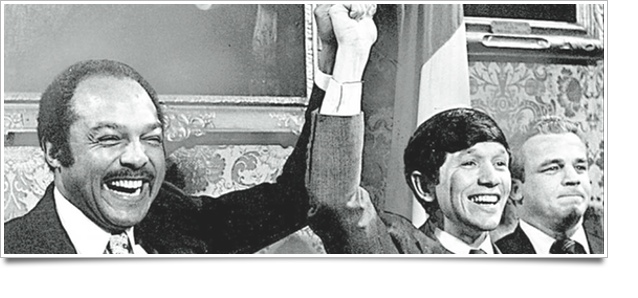

In the other major crisis, Carl Stokes turned a potential career-ending disaster into an example of how political skill can shift the blow to his tormentor.

Stokes’s problem resulted from a move he thought politically wise – the hiring of General Benjamin Davis as his Safety Director. Stokes always had trouble with the mostly white Cleveland Police. They didn’t accept him as mayor. Familiar?

He thought the police had to respect the authority of a general and that a black man in command of the mostly white police force served the purpose with his major constituencies. It didn’t quite go as planned.

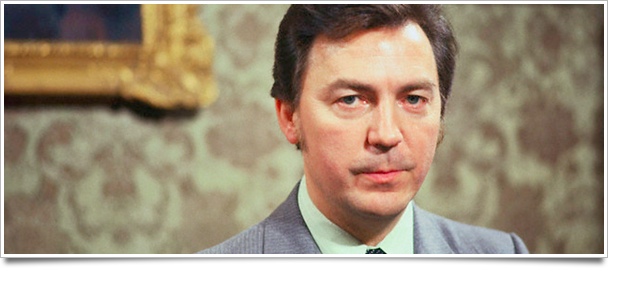

In his book, Promises of Power, Stokes quickly learned the mistake.

“Jim Stanton (Stokes bitter political rival and Council President) loved him, the newspapers loved him, the white community loved him. And “… the police fell madly in love with him.”

But Gen. Davis didn’t seem to understand either civilian life or politics. I had recently reported that the general had ordered hallow point bullets, also known as dum dum bullets, which explode on impact. Stokes, upon learning this, had his purchase rescinded. Black, he seemed to think White.

Signs Davis didn’t fit grew.

Stokes wrote: “At first, he kept an open door. When he discovered that the citizenry included bushy-hair, ill-spoken, angry young men wearing dashikis and carrying absolutely no respect for him, his position or his status, he changed his policy.” He shut them out.

The general was not accustomed to civilian life. Especially not in a big urban 1960s city rife with racial conflict.

It all came to a head for Stokes with a public relations punch to the solar plexus.

Davis in a hand-written letter declared:

“I find it necessary and desirable to resign as director of public safety, City of Cleveland. The reasons are simple: I am not receiving from you and your administration the support my programs require. And the enemies of law enforcement continue to receive support and comfort from you and your administration. I request your acceptance of my resignation at your earliest conveniences.”

The key few words were “… the enemies of law enforcement continue to receive support and comfort from you and your administration.”

Stokes’ description of this deserves a reading from his book.

The news media, of course, had a field day. It fit their image.

As Stokes put it, after just having had a public scuffle over a police chief, ‘This damn hero was accusing me of harboring criminals; suddenly all the racist rumors about me were confirmed.” Double trouble.

The media had one of its frenzy. After all, the respected general had accused the first-term mayor of harboring criminals. But he wouldn’t name them. That left it up in the air for more news speculation and frenzy.

Tom Guthrie, an assistant to publisher Tom Vail and someone reporters felt intolerant of blacks, rarely wrote in the paper. But he couldn’t resist. In an opinion piece he blessed Davis with “absolute integrity.” I wrote he apparently had “divined” this from Davis’s golf shots, which he advised were “right down the middle.” The general a golf partner of the editor. He called him “intellectually honest” and drove the point further saying the general probably couldn’t “tell a lie to save his life.”

It sounded like the beginning of a campaign.

Stokes, ravaged in the press, called on Davis to name names. He said the stolid military man wouldn’t budge. No names.

So Stokes named them himself, having had Davis tell him privately what he wouldn’t say publicly.

Stokes had, as he writes, whet the appetite for names.

And when he named them, it was game over.

They included the Council of Churches, the Call & Post, a black newspaper, the mild-mannered Rev. Arthur Le Mon, Baxter Hill, who ran a program in 1967 to keep peace in Cleveland, and a neighborhood settlement house. Not on anyone’s “wanted” list.

Stokes wrote that even Tom Vail, publisher of the Plain Dealer, “felt compelled to editorially lament the general’s failure to substantiate his charges.”

But as I read back on my coverage in Point of View of July, 1970, it appears that Stokes was even more politically astute than to merely undercut. The general, political novice remained mute before the avaricious press. So Stokes named the names himself taking all the air out of Davis’s attack balloon.

Some top Cleveland leaders were truly ready to put Gen. Davis forth as a mayoral candidate.

Stokes, realizing this, was setting a trap for Davis.

Here’s what I wrote in July, 1970:

“Davis began getting tacit support from parts of the media and the Democrat and Republican parties looking for a candidate next year. By the end of the week he (Davis) had the damaging endorsement of the American Independent Party of George Wallace.” And Even the Cleveland Patrolmen’s Association’s support.

“But why did Davis quit so suddenly and in a huff?”

Davis probably learned of attacks upon him being prepared at City Hall with the knowledge of the mayor. A report documenting requests for protection of blacks in Tremont revealed the failure of Davis to act. The report “would have severely criticized Davis.”

“Because of Davis’s lack of concern about attacks on blacks in Tremont, clergymen had to be recruited through the Council of Churches to patrol the area. The city community relations division also took an active role,” I wrote.

(Two weeks before I had written an issue devoted to the harassment of blacks in a ward governed by then Councilman Kucinich. Both he and Davis ignored the harassment blacks were suffering. White and black ministers patrolled the streets to help keep calm and protect black residents, living mostly in public housing.)

“Thus it was amusing, but not surprising, that among Gen. Davis’s ‘enemies of law enforcement’ were Rev. Le Mon, also head of community relations and the Council of Churches…”

All in all, I think Davis played right into the hands of a brilliant politician. Stokes went on to win re-election in 1971.

(I miss Carl Stokes. In this time of meek and weak politicians here and the “it is what it is” mayor. I long for mayors who pushed for change and had innate mindset for the underdog and poor people. I miss that part of Dennis, too. I hope he is writing a memoir beyond his excellent “The Courage to Survive,” which only covers his young life.)

* * *

Point of View articles dealing with both these Cleveland episodes from the 1970s can be found on the Cleveland State University’s Memory site here. The CSU memory site has made all 32 years of my newsletter available and searchable. It’s a history unlike the conventional media of the time.

Roldo Bartimole has been reporting since 1959. He came to Cleveland in 1965 to report for the Plain Dealer where he worked twice in the 1960s, left for the Wall Street Journal in 1967. He started publishing his newsletter Point of View in 1968 and ended it in 2000.

Roldo Bartimole has been reporting since 1959. He came to Cleveland in 1965 to report for the Plain Dealer where he worked twice in the 1960s, left for the Wall Street Journal in 1967. He started publishing his newsletter Point of View in 1968 and ended it in 2000.

In 1991 he was awarded the Second Annual Joe Callaway Award for Civic Courage in Washington, D.C. He received the Distinguished Service Award of the Society of Professional Journalists, Cleveland chapter, in 2002, and was named to the Cleveland Journalism Hall of Fame, 2004. [Photo by Todd Bartimole.]