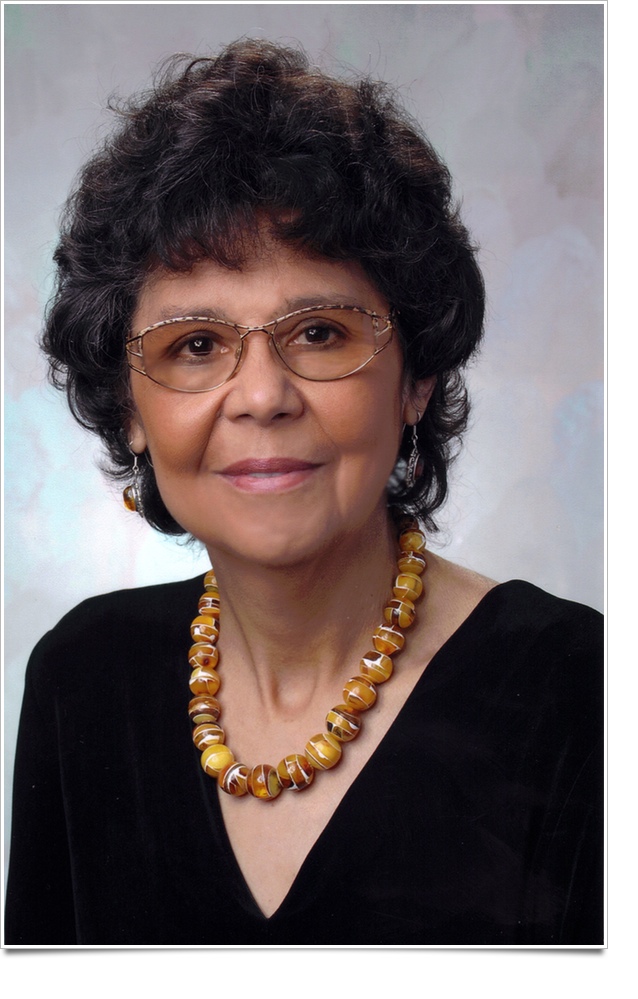

By C. Ellen Connally

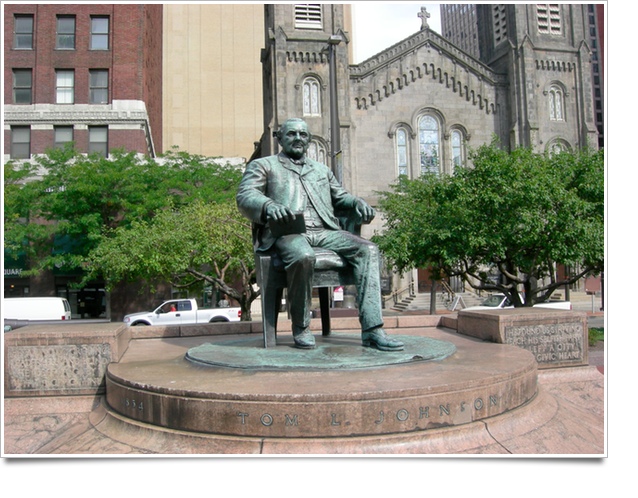

Cuyahoga County Councilman Dan Brady is a great admirer of Cleveland’s 35th mayor — Tom L. Johnson. Brady is not alone in his admiration of the man who served as the Mayor of Cleveland from 1901 – 1909. Johnson, both literally and figuratively, brought Cleveland into the 20th century. His accomplishments are such that many historians rate him not just Cleveland’s greatest mayor but America’s greatest mayor — ever. That is why a grateful Cleveland erected a statue of Johnson on the northwest quadrant of Public Square in 1916. In keeping with the way Americans of the day honored their dead, Cleveland wanted a bigger than life image of the man they wished to honor — one that would last for the ages.

Johnson, a millionaire businessman and former Congressman, came to govern a city that had few paved streets — he paved them and kept them clean. He hired police and firemen and picked up the garbage. The drinking water was putrid, so he started construction of “the crib” three miles off the city in Lake Erie to improve the water. People died because of poor and unsanitary health conditions; he reformed the Health Department and helped to eradicate small pox and tuberculosis and in passing cleaned up unsanitary barbershops.

Like other major urban areas, hundreds of homeless youth roamed the city and contributed to the rising rate of juvenile crime. He opened the Boy’s Farm in rural Hudson to provide a home, life on a farm, and structure to the lives of these abandoned youths.

He went to the Workhouse at 79th and Woodland and found it to be more of a dungeon than a jail. He ordered prisoners released and cleaned it up. Cleveland had lots of parks at the turn of the 20th century but it also had lots of KEEP OFF THE GRASS signs. The signs came down. By the middle of Johnson’s term, 3.5 million people had visited at least one of the city’s parks. In an age before automobiles, when urban mass transit was privately owned, Johnson created publicly owned transit that provide reasonable fares for riders who suffered for years as victims of streetcars owners who often gouged working people whose only means of transportation to and from work was the streetcar lines.

If you have been to the new Convention Center you also have Johnson to thank for that. It was his plan for public buildings around an open public space — a plan that became nationally known and acclaimed — that located the new city hall, courthouse, public library, public auditorium and federal building on what Clevelanders now know as the Mall. The Group Plan, started in the Johnson Administration, controls the use and look of the Mall today.

A recently proposed reconfiguration of Public Square made no reference to the fate of the statue of Johnson. That is what sent Dan Brady into high gear. As a former Cleveland City Councilman, State Representative and political activist par excellence, he is no stranger to picket lines and demonstrations. As he voiced his concern about the fate of the statue of his idol, his face reddened and his Irish was clearly up — all of this spoken under a picture of Tom Johnson that hangs in his office.

The manner in which Americans remember past leaders has changed over the last 100 years or so. For much of the 19th and early 20th century Americans built majestic monuments and statues ala the Lincoln Memorial, the towering Garfield Monument, the stately McKinley Memorial in Canton and the last of the great presidential memorials, the Harding Monument in Marion, Ohio.

Seven miles from the statue of Johnson at University Circle stands a towering image of another famous Clevelander, Mark Hanna. Four years after his death, a circle of friends and admirers engaged one of the world’s most respected sculptors, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, to create a depiction of their hero. Hanna, a man of great wealth — he went to high school with John D. Rockefeller — and political skill and influence — he got fellow Ohioan and close friend William McKinley elected President — is credited with the creation of the modern day presidential campaign.

After a stint as Ohio Senator from 1897 to 1904, Hanna could have been elected to the White House but for his untimely death from typhoid fever in 1904. No matter what the weal stream of admiration and affection for Hanna in 1904, it is unlikely that one in ten thousand drivers who pass his image today, located catty-cornered to the Martin Luther King Library and adjacent to Stokes Boulevard, could name the person depicted or perhaps even cares — which is seemingly not unlike the fate of the Johnson statue.

By the middle of the 20th century, the nation and Clevelanders had changed the manner in which they honored their native sons — and a few daughters. Statues and large monuments were out. The naming of a building or a place was in. Cleveland now sports the Frank J. Lausche State Office Building; the Anthony J. Celebrezze Federal Building; Voinovich Park and the Michael R. White Elementary School. (Miles Standish lost out to White.) Hopkins Airport and Burke Lakefront Field honor the legacy of a City Manager and a mayor. And let us not forget the Carl B. Stokes Federal Court House, the Louis Stokes Veterans Hospital and a plethora of other Stokes namesakes along with an ever growing number of memorials to the late Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones.

As the memory of Johnson faded so did plans for a more massive memorial. One hundred years after his death, his contributions to the City are nearly forgotten. Now he sits alone, accompanied by pigeons, a few lunch time office workers and the ever present homeless at night. In life he went from great wealth to financial ruin at the time of his death. His image in the memory of Cleveland appears to mirror the reality of his life.

If the plans to reconfigure Public Square attempt to alter the monument to Cleveland’s greatest mayor, Dan Brady should not be alone in mounting a protest. The statue of Tom Johnson should stay and stand as a monument to the achievements of the mayor who brought Cleveland into the 20th century. Cleveland and the nation should continue to remember our past with dignity and old fashioned class — classier than a chandelier at Playhouse Square. Tom Johnson would have wanted it that way.

Inscription on the statue of Tom L. Johnson

Beyond his party and beyond his class

this man forsook the few to serve the mass

He found us groping leaderless and blind

He left us a city with a civic mind

He found us striving each his selfish part

He left a city with a civic heart

And ever with his eye set on the goal

the vision of city with a soul

[Photo: EurekaLott]

C. Ellen Connally is President of the Cuyahoga County Council (Democrat – District 9) and a former Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. She holds a BS from Bowling Green State University; a JD from Cleveland State University; a Master in American History from Cleveland State University and is a PhD Candidate in American History from the University of Akron.

C. Ellen Connally is President of the Cuyahoga County Council (Democrat – District 9) and a former Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. She holds a BS from Bowling Green State University; a JD from Cleveland State University; a Master in American History from Cleveland State University and is a PhD Candidate in American History from the University of Akron.

2 Responses to “HISTORY: Remembering the Past – The Stature & Statue of Tom L. Johnson”

Michael Baron

If you would like to read more about Tom L Johnson, Marcus Hanna and some of the other people mentioned in this essay, please come to http://www.teachingcleveland.org

Greg Squires

I loved the tribute to Johnson. Though I left Cleveland many years ago, I still consider it my hometown. (I was in Cleveland Municipal Stadium when the Browns shut out the Colts 27-0 in 1964 and have been a long suffering fan ever since.) I have a poster hung in my office with four smokestacks and the following quote, “I believe in municipal ownership of all public service monopolies…because if you do not own them they will in time own you. They will rule your politics, corrupt your institutions and finally destroy your liberties.” Tom L. Johnson, Mayor of Cleveland, 1901-1909

Greg Squires