Reviewed by Larry Durstin

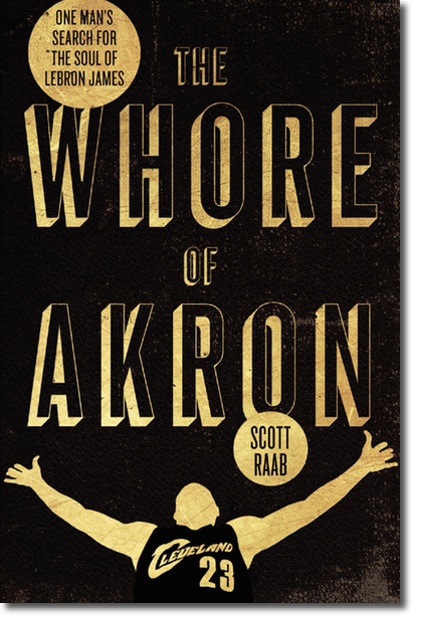

In its assessment of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, the Saturday Review observed, “who touches this book touches living tissue.” These same words could be applied to displaced Cleveland native Scott Raab’s remarkable The Whore of Akron — a visceral and raucously funny rant that’s more about Raab himself than it is about his target of disdain, LeBron James. And that’s a good thing, because less is more than enough when it comes to the duplicitous hoopster.

This is also perhaps the best book – along with Fred Exley’s A Fan’s Notes (1968) – ever written about the ragged world of sports obsession. But unlike Exley’s melancholy depiction of a man descending into madness upon realizing he is doomed to be nothing more than a spectator, The Whore of Akron is about Raab being regenerated by his choice to become an active participant in his fate as a long-suffering Cleveland sports fan and to wage a one-man crusade against the seditious James.

He writes, “Every man has a mission, a calling, a higher purpose and if he lives long enough life itself will thrust that mission upon him. Not in a moment of blinding insight… but rather as erosion. Surfaces wear away; the center crumbles; the things that once seemed vital prove their essential meaninglessness as years go by and what’s left – what is finally revealed – turns out to be the reason God breathed life into our very soul. My mission is to bear witness… To Cleveland. To the faith, hope and hunger that bind the soul of a people to their home. To the transcendent glory of sport and its spirit, fierce and pure… To LeBron, who once seemed to embody that soul and then betrayed it. And above all, to the Cleveland fans, the veritable nation of Job, whose heart burns yet through all the heartache and scorn.”

But this particular mission-of-no-mercy is not done atop a sleek steed nor is it akin to the oft-times wimpy wallowing of the “Poor Us, Only in Cleveland” cliché merchandisers. This sojourn is more the valiant, tortured shamble of a wizened warrior whose life is pockmarked by drug dealing and addiction, small-time larceny, at-times morbid obesity, crippling mental and physical maladies and, perhaps most tellingly, the witches’ brew of Jewish atheism. Throughout the book, Raab’s profane/profound tale of weather-beaten woe wails loud and near-biblical via molten utterances that might just as well have been fueled by acid and washed down with Mad Dog.

You say you want what is now delicately termed a “dysfunctional” childhood? Try this one on for size. Scott and his younger brother once tried to kill their philandering father by throwing knives at him while he ascended the stairs to his home in the “hope of poleaxing his yarmulked skull with one of them.” This is the same brother whom Scott constantly beat up because he realized that if he started to punch the person he was furious at, his mother, he wouldn’t stop punching “until she was dead.”

This is the backdrop for the primal scream of rage Raab directs at James, whom he foresees ending up “in Dante’s ninth circle of Hell – at the very bottom – where the worst of sinners are encased in ice for the worst of human crimes: treachery.” Raab, who often cries openly and somewhat unashamedly over the decades of wounds he has suffered as a Cleveland sports fan, circles LeBron like a tear-stained vulture, following him through each horrific step he’s made over the past year or so – the ones that are branded into every Cleveland fan’s heart:

On his monumentally craven tank job in Game 5 against the Celtics – the last time James appeared in a Cavs home uniform – Raab writes: “LeBron James is a fraud. No guts, no heart… a feckless child stunted by a narcissism so ingrained that he’s devoid of the capacity to respond to failure with even a semblance of manhood.” On the infamous Decision, “When I see the footage of LeBron with the little boys and girls I am both sickened and enraged, Idi Amin. I’m watching LeBron, the last king of Cleveland, using children as props, as ornaments, as moral deodorant.” On LeBron’s much-anticipated return to Cleveland in a Miami Heat uniform last December – a game in which the Cavs were totally humiliated as James brazenly taunted his former teammates – and where this debacle ranks in the long litany of Cleveland sports tragedies, “Red Right 88 [a bitter Browns playoff loss in 1981] hurt more because it came first. Nothing to befall a Cleveland sports fan could ever pack the wallop of shock and disbelief I felt that day. Nothing could ever lay me so low. Nothing, that is until December 2, 2010.”

While focusing primarily on his grueling journey in search of James’ soul, and the numbing Cleveland-fan anguish he expresses with John Brown-like passion, Raab has plenty to say about other local heroes and villains: On former Cavs GM Danny Ferry, “The world’s only 6’10” midget.” On Cavs owner Dan Gilbert, “A house afire. Intense is far too mild a word: This Yid once got into a fistfight at a friend’s son’s bar mitzvah. My kind of guy.” On Gilbert’s explosive letter to Cavs fans excoriating James, “A Comic Sans yowl of betrayal mingling scorn, curse and random syntax to near-Wagnerian effect.” On James’ early career in Cleveland, “His vast sense of childish entitlement seemed to speak louder every season. But, lord, the sex was fine.” On legendary Browns running back Jim Brown, “His mustache is a coiled muscle that looks like it could lead the league in rushing.” On sitting near Miami GM Pat Riley, whom Raab brilliantly portrays as a vampire, “I can smell the dirt in his casket.” And on what he would do if he met the only other Cleveland sports figure comparable to James in villainy, former Browns owner Art Modell, “Maybe I would have throttled that kike bastard. Or maybe we would have wept together over the parcel of rue each man is doomed to drag to his grave.”

As he pursues the object of his obsession, Raab spends much of the time suffering from an excruciatingly painful back, literally dragging his considerable girth around on grotesquely swollen feet while periodically popping vicodin and valium. Along the way, Raab recounts, with electrifying insight, past and present instances of remorse, reconciliation, relapse, revulsion and, inevitably, a dare-not-to-mention-too-loud longing for simply the possibility of redemption – all crazy-glued together with the peculiar strand of tormented romanticism that perhaps only the bowed-but-not-broken Cleveland sports fan can fully fathom.

In the end, the Day of Reckoning finds Raab in Miami, “representing… with every Cleveland fan who ever lived” as the Heat are eliminated in Game 6 of a championship series in which a disgraced James played so terribly that he became something of a national joke.

Sweet Deliverance.

“It’s not nostalgia, it’s plasma,” Raab writes in describing the quiet rush of connection and warmth he experiences upon his frequent returns to Cleveland, a place he loves “with a patriot’s heart, not a schoolboy’s.” And because of the depth of that kind of devotion and perspective, The Whore of Akron provides exhilarating testimony to the healing nature of even a partial acceptance of one’s fate and the cathartic joy that can sometimes flow from communal suffering commingled with unconditional love.

If, as has been said, the best writing involves opening a vein and bleeding, then this book is the “living tissue” of an inspired writer doing some real serious Bloodwork – the kind worth savoring for a long time.

Larry Durstin is an independent journalist who has covered politics and sports for a variety of publications and websites over the past 20 years. He was the founding editor of the Cleveland Tab and an associate editor at the Cleveland Free Times. Durstin has won 12 Ohio Excellence in Journalism awards, including six first places in six different writing categories. LarryDurstinATyahoo.com

Larry Durstin is an independent journalist who has covered politics and sports for a variety of publications and websites over the past 20 years. He was the founding editor of the Cleveland Tab and an associate editor at the Cleveland Free Times. Durstin has won 12 Ohio Excellence in Journalism awards, including six first places in six different writing categories. LarryDurstinATyahoo.com