Artist Talk: Thu 5/9 @ 6-8PM

On view through Fri 6/7

The exhibition Falling from the Sky of Now is a landmark accomplishment for all involved. For artist Douglas Max Utter, it is a well-deserved tribute to a distinguished, ever-evolving career. For HEDGE Gallery and owner-curator Hilary Gent, it is a victory lap for its first decade of outstanding exhibitions in 78th Street Studios.

Though the exhibit fills all available wall space in spacious HEDGE, it is still only a sampling of Utter’s career, now in its sixth decade. Viewers are all but certain to discover a chapter from Utter’s career that they had not previously seen. A rarity for a commercial gallery show, the works are contextualized with essays by Gent, Christopher L. Richards, and William Busta. (Richards is curator and collections manager at ARTNeo, and William Busta is the retired proprietor of the Busta Gallery.) A more complete catalogue is scheduled for release in September.

The selected works showcase the artist’s experiments with styles and materials, and his treatment of the same topics at different stages of his life. Falling from the Sky of Now puts Utter’s paintings into conversation with each other, and affords us the privilege of eavesdropping.

Utter’s cultivation of a distinctive aesthetic is most apparent when viewers compare two paintings made 39 years apart, “Row Houses on Prospect Avenue” and “Winter Garage.” Domestic architecture is an unusual subject for Utter, a figurative painter. But in depicting subjects less emotionally charged than human faces, viewers can more easily appreciate the stylistic and technical aspects of his work.

When painting “Row Houses on Prospect Avenue” in 1963, Utter used broad brushstrokes and stark colors to bypass photorealism. The colors are not wholly naturalistic, but also not conspicuously stylized. Brick is red or yellow, tree bark is brown, the sky is blue. Its materials are conventional, oil on canvas.

“Winter Garage” from 2002 is hung immediately below “Row Houses,” and demonstrates Utter’s mature style. The titular shed appears abstracted into four rectangles: a white-and-brown one for the roof, two sepia ones representing walls, and another for the shadow the structure casts. It stands as the only clear object in a dark, snowy night. The flurries are white, the sky is chocolate brown. Some darker veins in the brown suggest trees stripped bare by frost. The painted surface is given texture by a mix of acrylics, latex paint, tar and shellac. The line between ground and sky is blurred, as are those between ambient air, snow, stationary objects and flying debris. Viewers feel as if they are trapped outside in a bitter cold night, groping towards any faint light.

“Cherubim” from 1977 places two peach-robed figures in a small grove. One wears a forlorn expression, the other an embittered one. With their eyes cast down, neither notices the Pentecostal flames above their own heads, or the angel to their right. The angel is one of the alien, unknowable creatures written about in Ezekiel. Its cape is blown by a wind that does not touch the trees’ leaves or men’s garments. An unreadable mask hides its face.

There is much in “Cherubim” to surprise viewers of Utter’s contemporary works. The scene’s pastoral setting and saturated color scheme bring to mind Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings. The cherubim’s mask would not have looked out of place in Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” Otherworldly imagery remains a feature of Utter’s painting, but now it resembles epic mythology less than it does uncanny dreams; a viewer might need to do a double-take before realizing anything is out of the ordinary. No gods or angels parade the earth. Instead, an octopus might take the place of a cat cuddling in a woman’s lap, or a bear might stand in for the artist, contented and encircled by grandchildren.

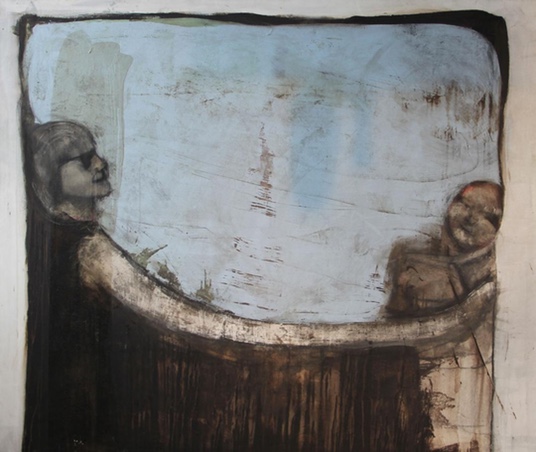

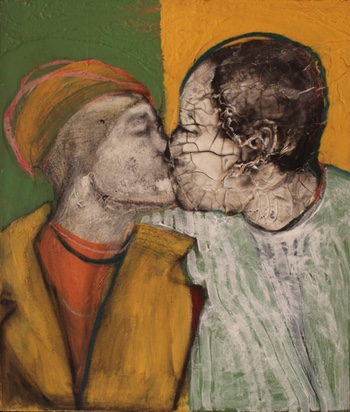

In recent years, not only has the content of Utter’s paintings have changed, but also the materials. While continuing to depict the figure, Utter placed his subjects in abstracted spaces. Landscapes and built interiors dissolve into backgrounds of colored planes. Sometimes, the human figures are crowded into the background, and have to peek through color fields to find the viewer. In recent decades, Utter has continued to paint with oils and acrylics, but also branched out into pastels and unconventional materials like latex, tar and spray paint. Each of these additions opens new directions for textural effects. Tar ripples, creating the illusion of movement. Latex pools into a glossy layer like ceramic. The “ceramic” sometimes cracks, making random lightning bolt patterns.

The cracking evokes the “fragmentation” and dissolution of memory over time. Utter’s use of color also suggests the imperfections of memory. Even when depicting contemporary subjects, Utter colors human flesh in grays like those of black and white photographs. Green, blue, yellow and red are the most common colors. The latter three of these hues are of course “primary,” implying that we are seeing the most basic elements of the depicted scenes. The events Utter remembers might not have happened exactly like this, but we can see everything about them that is essential.

The partialness of memory is on vivid display in “Childhood Migraine.” A toddler in overalls sits on a sidewalk running past ranch-style homes. Behind him, a man uses a muscle-powered mower to cut the lawn. Above them both, a propeller-driven warplane flies through skies, which glow red like an atomic blast. In the childhood memory, there is only play, and the intrigue of watching an adult at work. Only later did the painter learn what was happening “in the background” of postwar world affairs. Through the memory, we can recognize things the child could not have.

But Utter’s paintings memorialize happy occasions, too. Many of his paintings depict family members, sometimes taking personal photos as references. The happiness on display is not sentimental, not cheap. The easy affection Utter’s relations show each other could only be achieved through years of peaceful coexistence. They lean on each other with earned, casual trust, and a lack of pretense or defenses. In “Photo Booth” from 2008, a man and woman sit side by side and lean in to kiss. The image suggests not eroticism, but a spontaneous act of mutual devotion. A woman lounges hammock-style in 2002 “The Long Touch,” extending an impossibly long serpentine arm to pat a chubby infant.

Utter’s depiction of touch conveys affection, but so does his portrayal of isolation. The most wrenching piece in the exhibit must be 2015’s “Wisconsin Car Crash.” On that canvas, space is fully three-dimensional. Wheat and grass extend to the horizon; in the foreground, two smashed cars lie on the road. Wolves stalk towards the collision site. To their right, space splits. Gone is the sunny pastoral day. The world is black here. The only visible objects are defined in white chalk: power lines, an alert terrier, and a man sitting on the pavement with his legs outstretched. The blackness is the veil of death—Utter says that the scene memorializes the death of an uncle in an auto accident. The ghostly figure is present, but inaccessible. Memory can comfort at a distance, as it does in “The Long Touch.” But it also is what makes possible yearning for who we have lost.

Utter will give an artist’s talk May 9 from 6 to 8 p.m. at HEDGE. Falling from the Sky of Now will run through June 7 at 1300 West 78th St., Suite 200. For more information, call 216-650-4201 or go to hedgeartgallery.com.

[Written by Joseph Clark]

One Response to “Landmark Show Looks at the Career of Cleveland Artist Douglas Max Utter”

John Stickney

Douglas Max Utter is a true artist, his work is always worth a long look.